The golden years of natural gas abundance are off and running, with export projects, new industrial proposals, new power generation use, and expanded transportation use - all building on a perception of long-term abundant supply at reasonable prices. Does it all work out in the end? Do supply and demand balance at stable, affordable prices, even with a lot more demand? Today we examine the likelihood that gas producers can provide adequate supplies without causing significant upward pressure on prices.

Daily Energy Blog

This winter the Northeast US is being blasted with record cold weather. As a result, daily natural gas prices in both New York and New England have spiked more than $30/MMBtu above the US benchmark at Henry Hub, LA. But the average price you’ll pay for natural gas in the region will likely depend on whether you root for the New York Giants or the New England Patriots. With their dismal records and embarrassing mistakes, it’s not easy being a Giants (or Jets) fan these days. But on average – thanks to new gas pipeline capacity added this past fall, natural gas prices in New Jersey and New York have remained less volatile relative to US benchmark Henry Hub, LA than prices in New England. That is because the six-state region continues to suffer from woefully inadequate gas transmission infrastructure. Today we begin a two-part analysis of the still-stalled effort to deliver more supplies to gas-hungry New England.

As North American supplies of natural gas continue to grow, more industrial, commercial, institutional and residential customers who do not burn natural gas for heating or process use want to participate in the economic savings associated with natural gas versus alternate fuels such as heating oil or propane. Complications in the process of installing pipeline infrastructure are slowing the rollout of direct gas line service. Today we describe natural gas distribution alternatives.

While most of the country is enjoying the benefits that low cost North American supplies of natural gas bring to local and regional economies, many parts of the Northeast US and Atlantic Canada are still heavily reliant on expensive oil-based products for residential, commercial and industrial use. That is in spite of the proximity of burgeoning supplies of natural gas in the Marcellus and Utica shale basins. The challenge in converting users away from oil lies in infrastructure build out and deciding who will pay. Today we begin a two part series on the slow conversion process and new solutions to supply natural gas to customers before pipeline infrastructure is built.

The hopes of Marcellus gas suppliers to move more of their product east are playing out in very different ways in metropolitan New York City and in New England. New pipelines to deliver gas from Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio to the Big Apple and its environs already are installed and operating, easing the metro area’s supply crunch and shrinking regional price “basis”. But plans to expand gas-transmission capacity to New England are stalled, and some gas users there are facing another potentially supply-constrained expensive winter. Today we begin a new series looking at why—for the foreseeable future at least--it’s better to be a gas user in New York City than Boston.

The golden years of natural gas abundance in which we find ourselves are sparking tremendous enthusiasm among potential users of the fuel, from power generators to major industrial companies, to exporters both current and potential. After all, a trifecta of cheap, abundant, and clean is hard to resist. But the big question is how supply and demand really shake out after everyone’s enthusiasm results in new and growing use of the resource. Is the natural gas industry going to be able to supply all the new demand without prices going up the way they have in the past, most recently hitting double-digits at Henry Hub just five years ago? The first step in order to weigh supply against demand is to have a plausible scenario of what that demand might be. What does it all add up to? So in today’s blog we will see how much demand we should be trying to meet, to be followed later by a next installment to see how producers might meet it.

Alaska officials, concerned the state’s once-dominant role in U.S. energy production will continue slipping, are taking a fresh look at helping to jump-start a combined natural gas treatment plant, gas pipeline and LNG export project that would free vast volumes of natural gas now stranded at the state’s North Slope. A new study commissioned by the state found that it could make sense for Alaska to take a 20% or higher equity stake in the project, but that there are significant risks the state would need to mitigate. Today we look at whether the 49th state can make a long-stalled plan by producers to move North Slope gas to market a reality by the mid-2020s.

The CME natural gas futures market has been trading in a narrow 40 cent range between $3.40/MMBtu and $3.80/MMBtu since the end of the summer. The onset of winter and the first storage withdrawals last week (according to EIA) have done little to jump start prices. The prompt Henry Hub futures market closed at $3.702 yesterday (November 21, 2013). The dominating story remains increased supply from new production. Today we look at how supplies are weighing on spot prices and futures market speculation.

With the electric power sector in many other states turning to natural gas-fired generation to replace retired coal and nuclear capacity, gas interests were understandably optimistic the same would happen in California when the plan to retire the 2,200-MW San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) was announced in June. But California’s aggressive efforts to promote renewable energy and combined heat and power (CHP), improve energy efficiency, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions make it likely utilities and independent power companies there will use less natural gas going forward—not more. Today in the second part of our of series on California gas demand we examine why gas use by large-scale power plants in the Golden State is likely to decline, why CHP-related gas use by commercial and industrial firms will rise, and why the state’s gas pipeline infrastructure may need beefing up.

The June 2013 decision by Southern California Edison (SCE) to permanently shut down its San Onofre Nuclear Generation Station (SONGS)—the largest power generator in the region—got the attention of the natural gas industry, and for good reason. Natural gas interests view gas-fired generation as the logical replacement for the now-gone 2,200 MW nuclear capacity, but many other forces are at work. In this two-part series we examine southern California’s electricity cunundrum, and how big a part natural gas is likely to play in keeping the lights and air conditioning on and the pool pumps pumping.

The two-unit, 2,200-MW SONGS facility for years was a linchpin in the region’s electric grid (see Play Me A Songs). A relatively low-cost, around-the-clock generator at a pivotal location, San Onofre provided critical voltage support—an electrical engineer’s way of saying it kept the grid on an even keel. Natural gas interests expect SONGS capacity to be replaced by gas fired generation. And gas will surely have a significant role in the electricity future of the Los Angeles Basin, San Diego, and California as a whole. But because of state policies and Federal rules, among other things, utilities and merchant power companies may well end up consuming less gas than they do now, and commercial and industrial firms may use more.

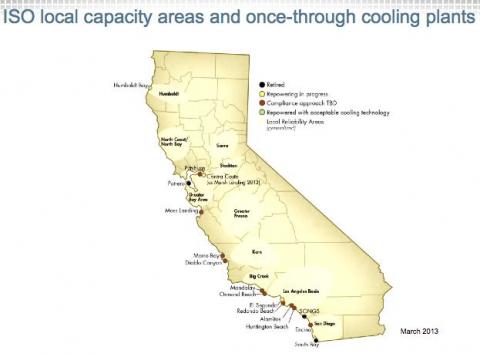

One big factor is California’s push for renewable energy and energy efficiency - including combined heat and power (CHP) plants that squeeze as much energy as possible out of each btu. Another is federal rules that will require about 3,800 MW of older gas-fired plants in southern California that use “once-through cooling” to be retired by 2020 (see Figure 1; note SONGS is just north of San Diego). Once-through cooling - like it sounds - releases cooling water after its been used only once, instead of recycling it—the preferred method now.

Figure 1

Source: California Energy Commission (Click to Enlarge)

Another 1,200 MW of gas-fired capacity in southern California is aging, inefficient and also likely to be taken offline within a few years. Regulators, gas-plant owners and others also need to wonder, how might the gas-delivery needs of power generators be affected by plans to export LNG from the region’s ports, or plans to pipe more U.S. gas south to Mexico?

In the first half of this two-part series we consider the closure of SONGS and how state policy and federal regulations are shaping natural gas’s future role in the southernmost third of the Golden State. In the second half, we will examine in more detail where gas demand is headed in California—and why—and what that means for gas producers with access to that market.

SCE decided in June it no longer made economic sense to hold out hope that SONGS units 2 and 3 could be restarted any time soon. Both units--which are co-owned by SCE (78.2%), San Diego Gas & Electric (20%) and the city of Riverside (1.8%)--had been taken offline in January 2012, Unit 2 for a planned routine outage and Unit 3 when operators detected a small leak in a steam generator tube. (Unit 1 was retired in 1992.) Subsequent testing found premature wear in tubes throughout both units’ steam generators, which had been replaced in 2009-10. It looked as if it might take years for federal nuclear regulators to approve fixing and restarting the units, so SCE and the other co-owners of SONGS decided it was better to pull the plug on them and work with state regulators to plan for replacing their output and reworking parts of southern California’s transmission system to keep the grid on an even keel without the nuclear capacity. As a result the power-supply situation in the LA Basin and San Diego this past summer was dicey, with utilities worried that the loss of a key transmission line or big gas-fired unit during a heat wave could cut off power to hundreds of thousands or even millions of customers.

The sustained low price for U.S. natural gas is doing exactly what it is supposed to do – attracting new demand into the market. Gas fired power generation, LNG exports, exports to Mexico and new industrial demand are all expected to contribute to demand growth for many years to come. But is this a permanent shift in the market, or could the new demand result in increasing prices that would quash the coming Golden Age of Gas? After all, the natural gas market has seen this movie before. We explored this possibility in our recent series titled “I’m a Believer”. But just because it is a possibility doesn’t mean it is going to happen that way, or even that it is likely. Because the world has changed. Today we begin a new series that explores the ways in which the natural gas world has changed, and why the gas market is very unlikely to repeat its roller coaster ride of the past three decades. It certainly doesn’t have to.

It seems like everybody and his uncle are planning new methanol production capacity in the U.S. The economics certainly are compelling. Low natural gas prices are attracting methanol projects like a magnet, especially to the Gulf Coast; domestic and foreign demand for methanol is rising; and methanol prices are as high as they’ve been in five years. But companies are always looking for an angle, a competitive edge, a chance to make their project the most cost-efficient—and profitable—of all. Today, in “Cheap Trick: ‘I Want You to Want Me(thanol)’”--we consider Valero Energy’s methanol initiative and its cheap trick: a plan to add 1.6 million to 1.8 million tons per annum (MMtpa) of methanol capacity for an investment of only about $700 million. That’s around half what it would normally cost.

For decades natural gas flows have moved to the huge Northeast demand region from the Gulf, Canada, Rockies and Midcontinent. Now those flows are being reversed by the Marcellus and Utica plays that will soon be producing more gas than the Northeast can use. How do the pipelines that serve the region deal with this transition commercially? Operationally? Physically? Today we will explore these questions and consider several terms that have become all-important in this upside-down gas world – backhauls, reversals, and null points.

Chemicals, gas-to-liquids (GTL), steel and other industries that consume large volumes of natural gas either directly or as a fuel, expecting the new era of low and stable gas prices to continue are planning tens of billions of dollars in new or expanded facilities in the U.S. But how many of those plans will become a reality? Could the much-anticipated industrial renaissance be undermined by the higher gas prices that might come with the approval of a few more LNG export terminals, new environmental regulations that spur still more gas-fired power generation, and higher natural gas exports to Mexico? Those are critically important questions to gas producers and marketers, who are struggling to figure out just how quickly—and how much—demand for gas will rise. Today we continue our exploration of industrial demand for natural gas.

Reversing the direction of flow on the eastern third of the Rockies Express (REX) pipeline would have a profound effect on natural gas markets throughout the industrial Midwest and the Midsouth. Not only would the plan significantly expand the regions’ access to gas from the Utica and western Marcellus shale plays, it would further erode the market shares held by traditional suppliers to those regions. In this Part 3 of our series on the REX reversal we examine how moving large volumes of now-constrained gas west from southwestern Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia would fundamentally change regional gas flow patterns, basis relationships, and even the operations of many pipelines.