As mightily as U.S. LNG exports have impacted global trade dynamics, so have U.S. natural gas flows been reshaped by the pull toward Gulf Coast export terminals. The next new terminal on deck is Venture Global’s enormous Plaquemines facility in Louisiana, which could begin taking feedgas as early as late fall 2024 and will eventually ramp up to more than 2.6 Bcf/d. For Southeast Louisiana, home to a massive industrial corridor along the Mississippi River as well as the U.S. natural gas benchmark Henry Hub, the introduction of such a huge source of demand will change how gas flows into and out of the region — with knock-on effects across the Gulf Coast. In today’s RBN blog, we’ll turn once again to our Arrow Model to help illuminate what the path forward may look like.

In our first blog in this series, My Aim Is True, we introduced the concept of the Arrow Model — a proprietary RBN analytical framework that organizes Texas and Louisiana into pipeline “corridors” that can be used to assess changes in regional inflows and outflows via groups of pipes that serve similar markets from comparable supply sources. These pipeline corridors are aggregations of pipelines connecting relevant market hubs — some within Texas and Louisiana and others outside the two states.

We also identified the LNG corridors through which gas exits the Gulf Coast. That brought us to a key takeaway of Part 1 — that we would see a mid-decade tightening in Louisiana gas markets relative to Texas. As we get down below the state level, into the more granular regional levels within Louisiana and Texas, it becomes increasingly challenging for anybody without a robust analytic framework to accurately parse out what’s going on. That’s because at the state level we can see aggregate supply and demand statistics from the Energy Information Administration (EIA) as well as detailed natural gas flow statistics for FERC-regulated interstate pipelines. (See Shall We Gather at the River for a disambiguation of interstate and intrastate gas pipelines.) Within a state, particularly ones as big as Texas or with as many legacy gas pipelines as Louisiana, modelling how gas flows becomes much more interesting. At RBN, we refer to this as the “big circle, little circle” problem; meaning that it’s much easier to develop a directionally correct model for a large geographic area than it is for a much smaller one. But that’s just exactly what we will do in this and subsequent pieces concerning the Arrow Model.

Let’s start our examination of some of the key market areas across Texas and Louisiana and explain how the arrow flows are changing and what it means for basis differentials.

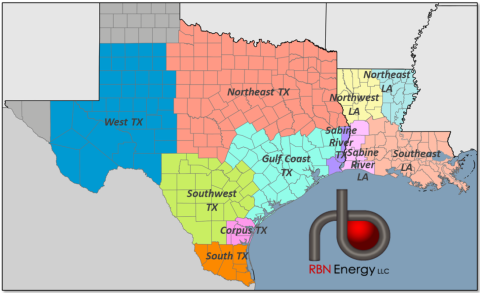

In our Arrow Model, we aggregate gas production, demand and net outflows or inflows, over time, for 11 market regions — seven in Texas and four in Louisiana. As we set out in the intro, our focus for this one will be on Southeast Louisiana (light-orange region in Figure 1 below). More on it in a moment.

Other regions for which we’ve developed our outlook are, from West to East in Texas:

- West Texas (blue region in Figure 1), which includes Permian Basin production and is home to the Waha natural gas hub.

- Northeast Texas (salmon) — home to the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex, the Barnett Shale and also a huge chunk of production from the Texas side of the Haynesville/Bossier shale as well as the NGPL TXOK gas hub.

- Southwest Texas (green), through which Permian gas moves on pipelines, including Gulf Coast Express (GCX) and Whistler on its way to the Gulf Coast.

- South Texas (orange) where, as we’ve blogged recently, gas exports to Mexico are growing along with production from the gassier parts of the Eagle Ford, and that will soon be home to the NextDecade LNG export terminal.

- The Corpus Christi region (hot pink), in which Cheniere operates the large and soon-to-be expanded Corpus Christi Liquefaction terminal, is also home to the Agua Dulce hub.

- The Gulf Coast region (teal) contains the Houston Ship Channel (HSC) gas price hub and industrial corridor, the Katy storage area and, of course, the Freeport LNG terminal and is soon to be the destination of gas from the Matterhorn pipeline.

- Finally, we’ve recently split out the Texas side of the Sabine River (purple) from the rest of the Gulf Coast Texas region due to the massive changes to gas flows as Golden Pass and Port Arthur LNG come online over the course of the next few years.

Figure 1. Arrow Model Regions. Source: RBN

The Louisiana side is a little easier to describe than Texas, though not necessarily easier to model. We’ve explained the Louisiana regions and corridors previously in our Down By the Water series. Essentially, the Haynesville production region and net gas inflows from Texas are in the Northwest (yellow region), net gas inflows from large interstate and intrastate pipelines feed the Perryville supply hub in Northeast Louisiana (light blue region), and gas flows from the Northern part of the state into South Louisiana. Similar to Texas, we’ve recently tooled up to get more granular in our analysis of South Louisiana. With all of the new export facilities, particularly around Lake Charles and the Sabine River in Louisiana (pink region) in West Louisiana, we’ve split it from our analysis of Southeast Louisiana (light orange).

Of course, the Sabine River region doesn’t have a monopoly on new export capacity from the Bayou State. As previously mentioned, the next large new export facility will be Venture Global’s greenfield Plaquemines facility in Plaquemines Parish, LA, about 20 miles south of New Orleans. The terminal will use the same modular technology as Venture Global’s currently (still) commissioning terminal, Calcasieu Pass. Eventually, Plaquemines LNG (pronounced PLACK-a-min) could be as large as 20 MMtpa (2.65 Bcf/d), consisting of 36 electrically powered, mid-size modular liquefaction trains configured into 18 blocks. The liquefaction process will be powered by on-site, behind-the-fence, combined-cycle gas turbines (CCGT) with the fuel supply coming from pipeline feedgas and boil-off gas from the liquefaction process. That means that the feedgas demand for the terminal will exceed the nameplate export capacity.

Feeding the terminal will be a combination of new, expanded and repurposed existing pipelines that we described, at length, in Gotta Get Over, Part 3. Most importantly, Venture Global developed the Gator Express pipelines to serve as the facility’s header. The first phase of Gator Express consists of a 42-inch-diameter pipeline extending 15 miles that will move as much as ~2 Bcf/d north from offshore interconnects with Tennessee Gas Pipeline (TGP) and Texas Eastern Transmission (TETCO) to the Plaquemines terminal. The second phase of Gator Express adds another ~2 Bcf/d of capacity with an adjacent 12-mile segment extending from the TETCO interconnect to the terminal.

The Gator Express system will pull its gas from a host of interstate and intrastate pipelines that crisscross Louisiana. The network of natural gas pipelines in southern Louisiana, especially around the Henry Hub region, looks like a bowl of spaghetti when mapped at the state level. It’s developed that way as, first, natural gas was moving into the state from offshore production prior to being moved down the line to Northeast demand markets. What evolved over long years was a tangled web of pipelines. After that, the giant gas developments in the Haynesville and later Appalachia turned the gas flows around the other way (for more on the history check out our Blank Space series). And while that latter development didn’t result in a bunch of new pipelines in South Louisiana, it did completely reshape flows in and around the state and result in a plethora of debottlenecking projects.

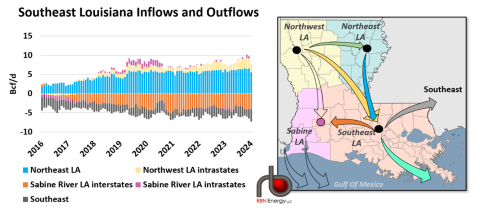

The beauty of the Arrow Model is that we’ve simplified that mess into just four corridors flowing into and out of Southeast Louisiana. Shown in the schematic to the right in Figure 2, Southeast Louisiana is a net receiver of gas from Northwest and Northeast Louisiana (represented by the yellow and blue arrows, respectively). At the same time, in aggregate, gas moves out of the region to the Southeast U.S. (gray arrow) and also West to the Sabine region (orange arrow). Those net natural gas flows are shown in the graph to the left in Figure 2 and differences between net inflows (bars above the zero line) and net outflows (bars below the zero line) are balanced by local production, demand and storage (not shown on the graph). As LNG exports have ramped up in the state since 2016, net inflows, primarily from Northeast Louisiana (blue arrow and bars) have grown from about 2.1 Bcf/d in 2016 to 8.4 Bcf/d on average in 2023. Much of that gas then went West to the Sabine LA region and through, also by displacement, to the Texas side of the Sabine. Net outflows westward from Southeast Louisiana on interstates and intrastates grew from less than a Bcf/d up to 3.7 Bcf/d in 2023 (orange arrow and bars) — and that number likely would have been even higher if not for the demand-dampening effect of the Freeport outages farther west.

Figure 2. Historic Gas Pipeline Flows Into and Out of Southeast Louisiana.

Source: RBN, Wood Mackenzie

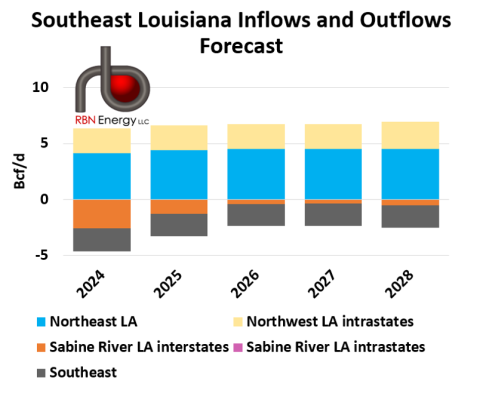

The final arrow that we haven’t yet mentioned is the teal one at the bottom which will represent the LNG exports from Plaquemines. As Plaquemines ramps up beginning this year, more gas will be needed to stay in the Southeast. On top of that, industrial demand, including new ammonia facilities around Baton Rouge, will also require more gas. As a result, net flows to the Sabine region are forecast to decline from an estimated 2.6 Bcf/d in 2024 (orange bar segment to the left of Figure 3) to just 0.5 Bcf/d by 2028 (orange bar to right). That happens even though there will be over 12 Bcf/d of LNG export capacity operating in the Lake Charles/Sabine River regions by the end of the decade — the impact of which will be felt all the way down to the south of Texas.

Figure 3. Forecast Gas Pipeline Flows Into and Out of Southeast Louisiana. Source: RBN

But that only scratches the surface of the story. It’s possible, despite the effects of the recent pause on LNG export permitting, that by the end of the decade more new LNG facilities planned for the Sabine region like Venture Global’s other behemoth, CP2, or Energy Transfer’s Lake Charles LNG, will be moving toward completion. If it plays out that way, gas prices in the Sabine region would rise relative to Southeast Louisiana and it’s possible that flows out of Southeast Louisiana might once again shift westward.

And what would happen to prices in our Southeast Louisiana region? Well, because it is home to the Henry Hub, prices in the region will generally be close to the benchmark. However, when Plaquemines comes online there will be less slack in the Southeast Louisiana system to absorb tightening in neighboring markets, which could lead to some additional volatility in the benchmark itself. Real separation starts to show up for gas moving farther east toward Atlantic markets (a phenomenon felt acutely in the summer of 2022) and to the west in the Louisiana region near the Sabine River.

For a deeper dive on the all-important Sabine River region and what the surge in export capacity will mean for gas flows and prices around that area, RBN will host a webcast, including a Q&A session, this Thursday, February 22, at 1:00 PM CST for our Backstage Pass subscribers. Click here for more details and registration.

For those interested in how the guts of the Arrow Model work, we’ll be diving into the nuances of natural gas pipeline analysis and modelling in our upcoming NATGAS Master Class on April 10th. This event provides a unique opportunity to gain a comprehensive understanding of these crucial topics and explore their practical applications through insightful presentations, interactive exercises, and discussion. Click here for more information and to register.

“Follow Your Arrow” was written by Brandy Clark, Shane McAnally, and Kacey Musgraves. It appears as the 11th song on Kacey Musgraves’ major-label studio album debut, Same Trailer Different Park. Released as the third single from the LP in October 2013, it went to #10 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs and #60 on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles charts. The lyrics follow the theme of remaining true to yourself and following your dreams. There are two controversial lines in the song, one supporting the LGBT community, and the other supporting smoking pot. When Musgraves performed the song at the 2013 Country Music Association Awards show, they censored the “roll up a joint” line because they felt it was too controversial for primetime television. Ten years later, the network would probably roll with it. Personnel on the record were: Kacey Musgraves (lead, backing vocals, acoustic guitar, whistling), Matt Stanfield (keyboards), J.T. Corenflos, Dave Levita, Rob McNelly, Kyle Ryan, Ilya Toshinsky (electric guitar), Misa Arriaga (acoustic guitar, ukulele, backing vocals), Jimmie Lee Sloas (bass), Fred Eltringham (drums), Russ Pahl, Bucky Baxter (pedal steel guitar), and Kree Harrison, Natalie Hemby, Shane McAnally (backing vocals).

Same Trailer Different Park was recorded between 2012-13 at Ben’s Studio, The Rackett, Sound Emporium, and Maverick Recording in Nashville. Produced by Luke Laird, Shane McAnally, and Kacey Musgrave, the album was released in March 2013 and went to #1 on the Billboard Top Country and number two on the Billboard 200 Albums charts. It has been certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America and won a Grammy Award for Best Country Album at the 56th Annual Grammy Awards. Four singles were released from the LP.

Kacey Musgraves is an American country music singer, songwriter, and record producer. She started her professional career as part of the child country music duo, Texas Two Bits. Musgraves released three self-produced independent albums in the early 2000s. She signed her first major label record deal with Mercury Nashville in 2012 and released her debut LP with them in 2013. She has released eight studio albums, one soundtrack album, four EPs, and 21 singles. She has won four ACM Awards, seven CMA Awards, and six Grammy Awards. She continues to record and tour.