Natural gas-fired power generation has always played second fiddle to hydropower in the Pacific Northwest, where dams in the Columbia River Basin typically supply well over half the region’s annual power needs. Gas takes on a more significant role, however, in years like this with lower-than-normal precipitation and hydro generation. And the ongoing phase-out of coal-fired plants in the Pacific Northwest is nudging gas closer to center stage—not just in 2014 but also over the long haul. Today we start a series examining the brightening outlook for gas use in the most hydro-dominant region in the US.

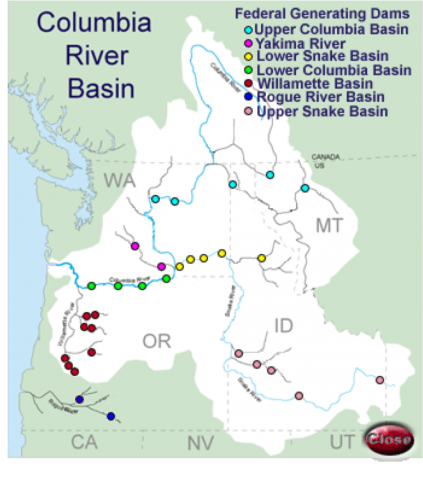

Oregon and Washington State represent the heart of the Pacific Northwest, but it is not uncommon to include northern California, Idaho, and Montana in the region as well, given their location and generally similar terrain. That broader definition also takes in the geographic reach of the 31 federally owned dams in the Columbia River Basin (see Figure 1), which together can generate up to 22 gigawatt (GW)—the equivalent of 20 nuclear reactors. (California also has major hydro assets, and imports a lot of hydropower from the Columbia River Basin dams; we will look into California’s hydro/gas situation—including its historic drought—in a later episode of this series.) The Grand Coulee Dam is by far the largest power generator on the Columbia River, accounting for more than 30% of the region’s hydro capacity. Many of the region’s other large hydro dams are located along the main stem of the Columbia as well; the rest are along the Snake River and its tributaries.

Figure 1

Source: Bonneville Power Administration (Click to Enlarge)

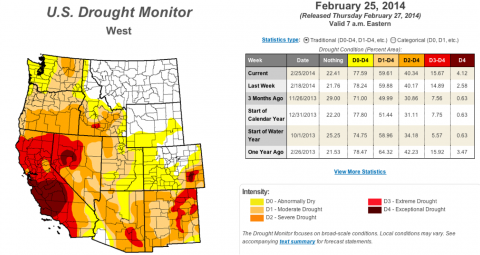

Oregon typically gets about half its electricity from hydro dams and about one-quarter from gas-fired plants, though in a wet year hydro can provide as much as three-quarters of the state’s power. Washington gets three-quarters of its power from hydro in a normal year, and even more in a wet one. The rest of the state’s power comes from a mix of coal-fired plants, gas units and the region’s lone nuclear plant. The degree to which the Pacific Northwest’s hydro facilities can meet the region’s power needs depends, of course, on how much upstream water is available, and that availability is largely dependent on how much snow falls each winter. This year, the news so far has not been good—from hydro’s perspective, that is. Precipitation for the hydrological year that started last October has been running at less than 70% of normal levels throughout most of the Pacific Northwest. The Snake River area in southern Idaho is experiencing what is officially referred to as an “extreme drought” (as is much of California), and almost all the rest of the Pacific Northwest is in a drought classified as either “moderate” or “severe” (see Figure 2). As a result, the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Northwest River Forecast Center says the water supply upstream of the Columbia’s Dalles Dam—the benchmark for such measurements--will be at only 94% of its normal level in the April-through-September period this year. It is worth noting that forecasts can change; 2012 seemed like a relatively dry year as of mid-February, but thanks to a few big snowfalls later that winter it ended up being the sixth wettest year since 1960.

Figure 2

Source: National Drought Mitigation Center (Click to Enlarge)

The current NOAA forecast for 2014 would make this year the 16th driest in the region since JFK was elected; 2010 was only slightly drier (it was the 14th driest since 1960), and in that very comparable year gas-fired units in the Pacific Northwest generated far more power than they did in 2012, which as we just noted turned out to be one of the wettest years on record. In Oregon, hydro plants generated 30.5 million megawatt hours (MWh) in dry 2010, and gas-fired units produced 15.7 million MWh; in wet 2012, hydro output rose to 39.1 million MWh, and gas-unit output fell to 11.6 million MWh, all according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). The hydro/gas dynamic was similar in Washington State. There, in dry 2010, hydro plants produced 68.3 million MWh and gas units 7.8 million MWh; in wet 2012, hydro output jumped to 89.5 million MWh and gas-unit output fell to 5.4 million MWh. As would be expected, gas consumption by the electric power sector rose and fell with gas-unit output. In Oregon, gas consumption by the sector totaled 108.4 Bcf in dry 2010; in wet 2012 it totaled only 82.0 Bcf; in Washington State, gas consumption by the electric power sector totaled 74.5 Bcf in 2010; in 2012 it dropped to 39.2 Bcf. Those are pretty big swings that can cause significant volatility in the natural gas market.

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article