The success of an LNG export project is founded on many things. Good connections to natural gas supply. Easy access to LNG buyers. A competitive delivered cost. Timing matters too, and may turn out to be a critical factor for Veresen’s Jordan Cove LNG export project in Oregon. Not only is it the first greenfield project to win the approval of the US Department of Energy (earlier DOE approvals went to projects to convert existing import terminals to export facilities), Jordan Cove also would be the first new LNG export terminal on the US West Coast—days closer to key buyers in the Asia/Pacific region than its Gulf Coast competitors. And it appears likely to beat out the first LNG export projects in British Columbia. Today in the first of a two-part blog series, we take a look at the Jordan Cove plan—its gas supply sources, the pipelines feeding it, the project’s economics, and its likely fate.

A race is on among prospective LNG exporters in the US and Canada to secure regulatory approvals (see The Molecule Laws – Part 1), lock in LNG buyers and gas suppliers, and build the needed infrastructure. Being among the first at the finish line is a do-or-die matter, because realistically there will be limits to the number of LNG export projects approved, the volume of LNG that will be allowed to be exported, and demand from major LNG buyers. LNG buyers in Asia, Europe, and Latin America have options--Qatar, Australia, and Malaysia among them—and, in their quest for sourcing diversity and low prices, they are constantly sizing up the North American LNG export projects under development to see how they might fit into their gas-supply mix.

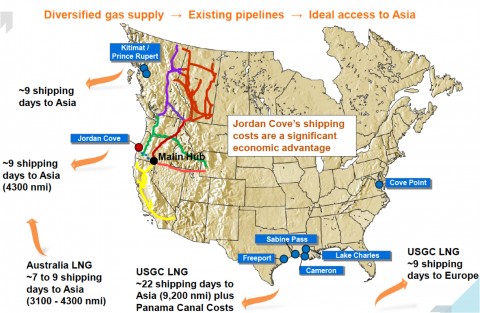

Jordan Cove is a 6 MMTPA (or million metric tons per annum - about 800Mcf/d) LNG export terminal (expandable to 9 MMTPA, 1.2 Bcf/d) to be built within the Port of Coos Bay on the Oregon coast. (The project was first envisioned as an LNG import terminal a few years ago, but the US and Western Canadian shale boom put the kibosh on that.) In March, Veresen, ,the project’s owner, a Canadian midstream natural gas infrastructure company, received DOE’s approval to export up to 800 Mcf/d of LNG to non-Free Trade Agreement (FTA) countries for 20 years. (That approval is critical for exports to the Asian market where only Singapore and South Korea are FTA countries.) Veresen this fall expects to get Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s approval to build Jordan Cove. If all goes according to plan, Veresen’s financial investment decision and construction start will come in the first quarter of 2015, and the first LNG will be shipped in late 2018 or early 2019. Figure #1, from a recent presentation by the owner, helps us tell the story.

Figure #1

Source: Veresen (Click to Enlarge)

The map shows the Malin gas hub in southern Oregon that will be the principal source of supply for Jordan Cove. Malin is well connected via existing pipelines to both Western Canadian and US Rockies gas supply areas. As we pointed out in Who Stopped the Rain—Natural Gas Gaining Market Share in Hydro-rich Northwest, there is 4.1 Bcf/d of existing pipeline capacity into the Pacific Northwest from Western Canada and 2.1 Bcf/d from the Rockies—up to 1.5 Bcf/d of the latter from Kinder Morgan and Global Infrastructure Partners’ Ruby Pipeline from western Wyoming to Malin. Additional pipeline capacity within the region is under development, including the 232-mile Pacific Connector pipeline (the dotted line between Malin and Jordan Cove) planned by a joint venture of Veresen and Williams Partners; it will move up to 1 Bcf/d from the Malin hub to Coos Bay. (In addition to receiving Rockies gas via the Ruby Pipeline, Malin receives Western Canadian gas via TransCanada’s 2.2 Bcf/d Gas Transmission Northwest (GTN) Pipeline. Jordan Cove has approvals from DOE and Canada’s National Energy Board to export up to 1.55 Bcf/d of Western Canadian gas to the US—more than enough to meet all of Jordan Cove’s needs, even at full build-out to 9 MMTPA.)

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article