Eager to boost oil and natural gas production, the government of Mexico is in the midst of a multi-year effort to introduce more private-sector involvement and competition. The hope is that a series of reforms will lead to more investment and—over time—a Mexican energy sector that more closely resembles that of Mexico’s amigos North of the Border. Today, we continue our look at the ongoing transformation of U.S.-Mexico hydrocarbon trade and what it may mean for energy companies on both sides of the Rio Grande.

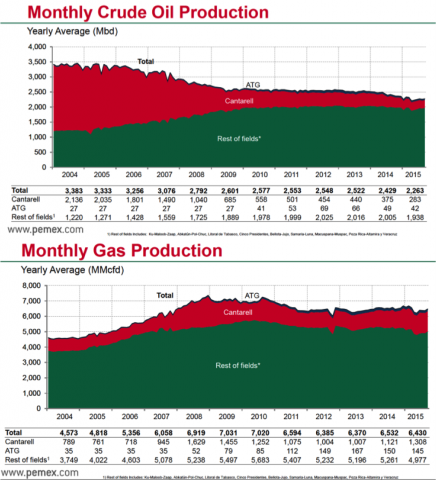

Since 2010, U.S. crude oil production has risen by 71%--from 5.5 MMb/d in 2010 to an average of 9.4 MMb/d in the first eight months of 2015, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). U.S. natural gas marketed production is also up: from about 61 Bcf/d in 2010 to 79 Bcf/d, on average, in the January-through-August period in 2015, again according to EIA. Over the same period, however, oil and gas production at Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex)—Mexico’s state-owned energy company and (since 1938) the only producer in that country—has slipped and stagnated. Pemex’s oil production averaged 2.6 MMb/d in 2010 (from a peak of 3.4 MMb/d in 2004, when its Cantarell field in the Gulf of Mexico was going great guns; see upper chart in Figure 1) and has fallen every year since; in the first nine months of 2015 it averaged 2.3 MMb/d.

Figure 1; Source: Pemex, Investor Day Presentation, October 2015 (Click to Enlarge)

Pemex gas production, meanwhile, has dropped from about 7.0 Bcf/d in 2010 to 6.4 Bcf/d in 2015’s January-through-September period (lower graph in Figure 1), even as demand for gas within the country has soared. (As you might expect, Mexican production of natural gas liquids is off too: from 377 Mb/d in 2010 to 330 Mb/d so far this year.) The U.S. and Mexico of course have different geologies and different magnitudes of oil and gas reserves, but there are similarities as well. For example, both countries have extraordinary shale oil and gas reserves; both also have been exploiting hydrocarbons beneath their parts of the Gulf (though Mexico’s focus has been on shallow-water finds). What many have suggested is that the real story behind Mexican production decline is the state-controlled nature of Pemex, and the financial and other pressures at Pemex that for years have 1) minimized investment in exploration/production of new oil and gas fields in the Gulf; 2) stymied development of northern Mexico’s potentially prolific Burgos shale region (just south of the Eagle Ford); and 3) slowed the pace of improvements to Pemex’s refineries, pipelines and other energy-related infrastructure. As we said in Episode 1, this combination of falling production and insufficient investment has only exacerbated the disconnect between the quality/volumes of (mostly heavy) oil Pemex is producing and its refinery configurations (which result in too much high-sulfur fuel oil and not enough high-value transportation fuels being produced).

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article