From the start of the Bakken oil production boom four years ago, a substantial portion of the associated natural gas produced has been flared, mostly due to a lack of gas gathering and processing infrastructure. Widespread flaring continues as the energy industry struggles to keep pace with the Bakken’s explosive growth. Finally, though, a confluence of events—new gas gathering and processing capacity coming online, new rules on flaring, and the emergence of new technologies for capturing and using stranded gas--suggests flaring activity may decline significantly over the next few years. In this new blog series, we examine what the energy industry, the government and entrepreneurs have been doing to help solve one of the shale era’s most persistent and high-profile problems.

As we said a while back in Why Will Bakken Flaring Not Fade Away?, flaring—while frustratingly wasteful—is done for both environmental and economic reasons. In any situation where natural gas (methane, a particularly potent greenhouse gas) would otherwise escape into the atmosphere (known as venting) it is less damaging to the environment if that gas is flared (burned). As for economics, flaring allows oil production to begin before pipeline infrastructure is in place to take away the associated gas that is produced. That is, if you drill a well for Bakken oil and start production, you can capture the oil in tanks and transport it to market in trucks and railcars until an oil pipeline is built, but you cannot do the same with the well’s associated gas. In the early years of the region’s oil boom, companies were wary to invest up-front in gas pipelines and processing plants until they knew for sure just how much gas would be produced. They have been playing catch-up ever since, and (as we will get to later) they finally are starting to close the gap between gas infrastructure needs and gas infrastructure in operation. In Set Fire to the Gas—The Fight to Limit Bakken Flaring, we explained that substantial flaring could occur even at wells that are connected to gas gathering systems and processing plants. Why? New wells connected to a gathering system produce gas at higher initial production rates and higher pressure. Gas from these new wells takes up pipeline capacity and knocks older, lower-pressure wells off the gathering system, causing their gas to flow back to the wellhead and require flaring. The solution to pressure problems that throw older wells off the gathering system is to increase compression in the system or to add additional capacity to existing pipelines by looping. Again, this is a constant game of catch-up.

|

|

N E W ! ! I’m Waiting For the Crude – Gulf Coast Crude Terminals and Storage We have just released our fifth Drill-Down report for Backstage Pass subscribers examining Gulf Coast crude oil flows, infrastructure projects and market implications. Subscribers get full access to all Drill-Down reports, blog archive access, and much more. More information on I’m Waiting for the Crude here. |

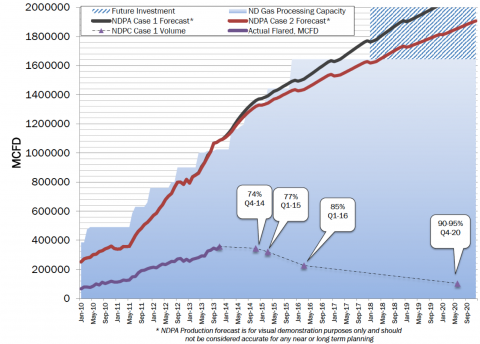

Due largely to still-rapid growth in Bakken oil production, actual gas production from the region now tops 1.1 Bcf/d (red line in graph in Figure #1); about 800 MMcf/d of that total is delivered to market and about 300 MMcf/d (purple line in graph) is flared for the variety of reasons we noted above. (Starting in January 2014, the red line represents the lower estimate of future production and the black line represents the higher estimate.) Our friends at Bentek Energy estimated recently that by the end of 2017 Bakken gas production will rise to 1.65 Bcf/d, with 1.2 Bcf/d of that to be delivered to market and 450 MMcf/d of it likely to be flared. That would keep the flare rate above 25%, and surely put added pressure on the industry to do more to reduce flaring. But according to the North Dakota Petroleum Council, it is possible that, with a concerted effort, the Williston Basin may already have reached what might be called “peak flaring”—that is, thanks to a variety of forces and efforts, the volume of Bakken gas flared could flatten out in 2014 and gradually decline over the following few years, and the portion of Bakken gas production that is burned off rather than delivered to market may fall from about 30% now to as little as 10% or even 5% by 2020 (dotted line in graph).

Figure #1

Source: North Dakota Petroleum Authority (Click to Enlarge)

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article