One of the biggest challenges to a significant expansion of the commercial hydrogen market in the U.S. is the lack of a comprehensive transportation network. That has spurred interest from utilities, government agencies and others interested in utilizing or repurposing parts of the existing (and extensive) natural gas infrastructure to ship hydrogen. But that approach comes with some challenges, starting with the significant differences in the physical and chemical properties of hydrogen and methane, the main component of natural gas. In today’s RBN blog, we’ll explain why moving hydrogen on the existing natural gas network — then storing and utilizing it — is no easy feat.

We’ve written extensively about hydrogen in the RBN blogosphere over the last couple of years as support for hydrogen as a potentially low-carbon alternative to fossil fuels across multiple sectors, including transportation fuel, power generation and energy storage, has waxed and waned. Our recent coverage has focused on the Biden administration’s efforts to build a market for clean hydrogen through the creation of several regional hubs (see The Contenders) and the potentially game-changing 45V tax credit (see The Name Game) as well as hydrogen’s use in the production of “electrofuels” (see Just A Little Bit Better) and the often-confusing hydrogen color scheme (see Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood). Even more recently, it was the focus of an 800-page report published by the National Petroleum Council (NPC) in April 2024 — “Harnessing Hydrogen: A Key Element of the U.S. Energy Future” — which included analysis from RBN on existing domestic hydrogen transmission and storage infrastructure (see our Harness Your Hopes series).

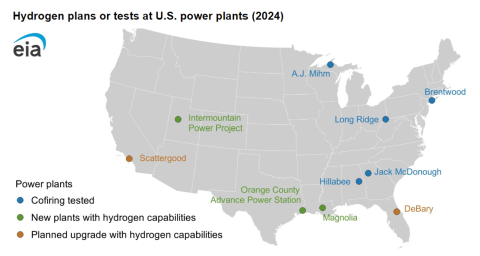

Natural gas is the largest source of energy used to generate electricity in the U.S., fueling 43% of power generation in 2023. When it comes to hydrogen, one of the areas proposed to have significant long-term potential is its use in gas-fired power plants, a process known as co-firing. As the percentage of hydrogen by volume in the blend increases, the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions decrease, although at a slower rate because hydrogen has a lower energy density than natural gas. (In general, a 20% hydrogen blend yields about a 7% reduction in emissions compared with 100% natural gas.) But hydrogen use is not widespread or used regularly in the gas-fired plants where it has been tested, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) said in a recent report. And while the primary reason for this is economic — natural gas is far cheaper to produce, per Btu, than hydrogen (despite substantial subsidies enacted during the Biden administration) — as we’ll get to, there are significant physical challenges as well.

Figure 1. Hydrogen Plans or Tests at U.S. Power Plants. Source: EIA

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article