This year’s polar vortex winter has once again demonstrated how New England power generators suffer from the region’s shortage of natural gas pipeline capacity during peak demand periods. The Catch-22 to-date has been that new pipelines won’t get built without firm, long-term commitments for pipeline capacity, which the New England power market doesn’t compensate generators for. Faced with rising demand and few alternatives to gas fired generation, the six state governments in the region are now proposing a novel fix: an electric-rate surcharge that would help guarantee pipeline developers the steady revenue they need to justify new projects. Today we examine the states’ plan and its prospects.

As we said in the first part of our recent series, Please Come to Boston—New England Needs More Natural Gas Pipelines, the region needs more gas for power generation, space heating and other uses, but it can’t benefit fully from ample and cheap Marcellus gas until sufficient pipeline capacity is in place to deliver gas when it’s needed—especially on the coldest winter days. The rub is that, as a rule, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) will not allow new pipeline projects to be built unless they demonstrate “market need” by securing binding commitments of 10 or 15 years or more for the capacity the new or expanded pipelines would provide —and of course, project sponsors themselves require similar economic commitments before they will invest. And, as we’ve said, the electricity market structure in New England does not provide sufficient incentives for generators to ante up the higher costs associated with firm contracts for gas delivery. The market does not give enhanced payments to power plants that virtually guarantee power when it’s needed, nor does the market sufficiently penalize generators for promising capacity and then failing to provide it. ISO New England is working on improving things, but it’s a complicated matter, largely because compensating gas-fired power plants for locking in firm pipeline capacity they may only need a few hundred hours a year would raise power prices for everyone. What it comes down to is this: unless New England can find a way to power through FERC’s pipeline-approval process, the region may face gas-delivery shortfalls for years to come.

|

|

A RBN Backstage Pass subscription gives you full access to RBN’s Drill-Down Reports, Blog Archive Access, Spotcheck Indicators, Market Fundamentals Webcasts, and Get-Togethers. Our newest RBN Drill-Down Report titled Like a Box of Chocolates – The Condensate Dilemma examines major developments in the world of condensates for the past few years and looks forward through 2018. More information on Backstage Pass here. |

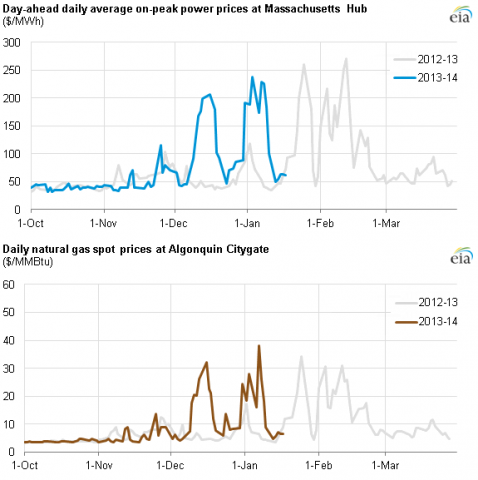

The lack of sufficient gas pipeline capacity to meet demand during periods of very cold weather this winter put a harsh spotlight on the issue. As usual, pipelines into New England filled mostly with gas destined for local distribution companies (LDCs) that long ago had locked in firm transportation contracts, and owners of many gas-fired power plants either scrambled for deliverable gas or switched to firing their units with oil or even jet fuel. Spot gas prices at the Algonquin Citygate spiked to several times their typical level, as did regional power prices (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Energy Information Administration (Click to Enlarge)

Officials in Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine were watching. Following up on a joint statement in early December, in which the region’s governors committed to collaborating to encourage development of needed energy infrastructure, the New England States Committee on Electricity (NESCOE) in late January sent a letter to ISO New England urging the grid operator to pursue FERC approval of out-of-the-box efforts to enable more bulk power and gas to be imported into the region. The bulk-power part of NESCOE’s plan calls for the development of new electric transmission capacity capable of delivering up to 3,600 MW of hydroelectric and other no- or low-carbon power to New England from Canada and New York. The gas part of the plan is revolutionary; it would have ISO New England ask FERC to allow pipeline projects to be financially underpinned not by long-term commitments for capacity but by higher electric transmission rates dedicated to help pay for the new pipelines. NESCOE, whose members are state officials appointed by the region’s six governors, was specific in its gas-pipeline goals. It said the additional pipeline capacity to be developed would be capable of delivering gas from the Ramapo or Wright gas hubs in upstate New York “or a similar facility” at prices reflecting no or minimal basis differential relative to Henry Hub, LA (the US benchmark natural gas delivery point). Further, NESCOE said new or expanded pipelines together would increase the amount of firm pipeline capacity into New England by 1 Bcf/d above 2013 levels by the end of 2017, or 600 MMcf/d beyond the roughly 400 MMcf/d in pipeline projects already under development. NESCOE said it does not have a single preferred mechanism for securing pipeline capacity through the higher electric-transmission rates it envisions, and will work with ISO New England, power plant owners and others on developing a structure that meets the needs and goals of the region’s electric system.

ISO New England gave an almost immediate—and very positive—response to NESCOE’s idea. It said the experiences this winter and last regarding gas pipeline constraints into New England and the resulting spikes in gas and power prices provide “just more evidence” of the need to expand the supply of gas into the region. It said that while raising electric-transmission rates would be a novel approach to spurring investment in gas pipeline, “it is a mechanism that could break the logjam that has stymied the level of natural gas pipeline expansion needed to meet the region’s needs.” If FERC says yes, NESCOE’s plan could be a real boon to one or more of the pipeline projects being considered, including Kinder Morgan’s proposed “Northeast Expansion,” which would provide a new, gas pipeline into New England from the west. That project would consist of a new, 150-mile pipeline from Wright, NY to Dracut, MA (north of Boston); the first 50 miles or so of the line (from Wright to extreme western Massachusetts) would run parallel to Kinder Morgan’s existing Tennessee Gas Pipeline (TGP), and the rest would cut a new path across the Bay State to Dracut (see Figure 2).

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article