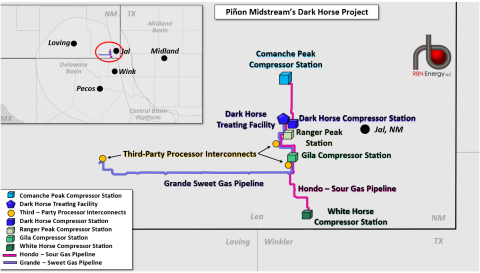

Some of the most prolific, crude-oil-saturated rock in the Permian’s Delaware Basin and Central Platform comes with a nasty complication — namely, associated gas with very high levels of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and carbon dioxide (CO2). But rather than walking away from all those potential barrels, one midstream company saw the treatment of high-H2S, high-CO2 gas as a market niche worth pursuing. Backed by commitments from Black Bay Energy Capital and an area E&P, Piñon Midstream has been expanding a system in southeastern New Mexico that not only gathers the super-corrosive gas and removes almost all the H2S and CO2, it also permanently sequesters the stuff deep underground through a pair of 18,000-foot-deep, Class II injection wells. In today’s RBN blog, we will provide an update on Piñon’s Dark Horse Treating Facility and the company’s plan for a further build-out of its sour gas system.

We first examined Piñon’s novel strategy in the aptly named Dark Horse blog almost two years ago. There, we said the gas that emerges from wells in U.S. shale plays differs widely in its characteristics and quality. For example, the “dry” Marcellus in northeastern Pennsylvania produces gas that is almost all methane, with only minute amounts of NGLs and contaminants, and therefore requires only minimal treatment before it’s fed into transmission pipelines. At the other end of the spectrum, a significant portion of the associated gas emerging with crude oil from portions of the Permian Basin in West Texas and southeastern New Mexico is classified as “sour” because it has high levels of H2S (a potentially deadly gas) and CO2 (the most prolific greenhouse gas, or GHG). Sour gas needs to be treated — a process often referred to as “gas sweetening” — to bring down the H2S and CO2 concentrations to acceptable levels. What’s acceptable? There’s some fuzziness and variety, but many midstreamers require that the gas flowing through their pipelines contain less than 4 parts per million (ppm) of H2S and no more than 2% or 3% CO2 content. (Most Permian associated gas comes out of the ground with minimal H2S and a CO2 content of only a few percent, though it’s not unheard of for some wells to be producing in excess of 4% H2S and/or 10% CO2.)

Typically, if the H2S content in the gas is relatively low — say, less than 1,000 ppm — the typical treatment would be to inject a scavenger, or specialty chemical, into the gas stream at the well pad to convert the H2S into a harmless product. Using a scavenger only mitigates H2S, however; any CO2 content above acceptable levels is removed at a downstream gas processing plant, and the typical current practice by processors is generally to vent the CO2 into the atmosphere — though as we said in The Air I Breathe, there are plans in the works to rethink that approach. The advantage of using a scavenger at the well pad is low up-front capital costs, but the volume of specialty chemical needed to remove the H2S rises with the associated gas’s H2S content and can become cost-prohibitive at high concentrations of H2S.

Another option — the one Piñon has been pursuing — is to construct scalable centralized amine treatment facilities in which the sour gas stream is run through an amine solution that absorbs the H2S and CO2 to produce a “sweetened” gas stream with only minimal volumes of H2S and CO2 remaining. The resulting “rich” amine is then routed through a regenerator to strip out the now-concentrated H2S and CO2 and thereby enable the amine to be reused. If the H2S concentration is low, the concentrated stream can be flared off along with the CO2 and other contaminants, but if the H2S content is high, flaring may well violate the air permit (and could even be dangerous, given the substance’s toxicity) and the H2S and CO2 are instead compressed and/or heated into a liquid and permanently disposed of through injection wells. Once the associated gas has undergone amine treatment, it is piped to a gas processing plant, where NGLs are separated from the natural gas.

As you might guess, many E&Ps avoid the areas where these H2S and CO2 issues would be the most serious. Still, many of these areas — including parts of Lea County in southeastern New Mexico, where Piñon’s work to date has been focused — also offer some of the best rock in the Permian, with exemplary initial production (IP) rates for crude oil and relatively low gas-to-oil ratios, or GORs (compared to the rest of the gassy Delaware Basin).

Figure 1. Piñon Midstream’s Gas System. Sources: Piñon Midstream, RBN

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article