Two maritime passages long regarded as essential shortcuts in the complex world of commodity shipping have become a lot more challenging to navigate. Transiting the Red Sea has turned potentially deadly because of geopolitical tensions, while severe drought has critically reduced operations at the Panama Canal. Combined, these issues are being felt across the energy industry, impacting U.S. and foreign producers and shippers, redrawing trade flows, extending voyage times and, ultimately, raising transportation costs. In today’s RBN blog, we’ll examine and quantify the extra time and costs that shippers of U.S. crude and refined products must bear when using alternative routes.

Before we drill into those expanding shipping costs, let’s look closer at what’s going on in the Red Sea, which is connected to the Mediterranean Sea by the Suez Canal. Since the Israel-Hamas war began in October, Iran-backed Houthi radicals based in Yemen have stepped up attacks on commercial vessels on that route in response to Israel’s military campaign. The rebel offensives have successfully targeted several ships but a few oil-related incidents have caught the world’s attention. Among the recent developments:

- In January, Houthi insurgents fired a missile that damaged the Trafigura-booked Marlin Luanda, an LR1 ship that can hold as much as 700 Mbbl of oil. It was carrying naphtha that had loaded in Greece for delivery to Singapore. It had transited the Suez Canal and the Red Sea to enter the Gulf of Aden, off southern Yemen, when the attack occurred. After the incident, it arrived February 11 at Fujairah in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), where it transferred its cargo to another oil tanker, the Marlin Lehavre. The damaged vessel was then moved to Dubai.

- In December, Norway’s Equinor had booked the Sonangol Cabinda, a Suezmax capable of carrying 1 MMbbl of crude, which loaded in Texas for supply to the west coast of India. After clearing the Suez Canal, it was headed for the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb (which separates the Red Sea from the Gulf of Aden) to reach its destination. In the middle of the Red Sea, it made a U-turn for safety reasons, completing its journey thereafter.

- In an example of preemptive action, the BP-chartered Aigeorgis, which can haul as much as 750 Mbbl of oil products, took the trip around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope in December after loading at Jamnagar, India, for its voyage to Texas. The ship was laden with vacuum gasoil (VGO) and the major would have typically used the Suez Canal for that route.

BP isn’t alone in its cautious approach. For some months, several commodity companies and shipping firms have been announcing plans to avoid the Red Sea area altogether to ensure the safety of their crew, cargoes and carriers, with little sign that the attacks would abate anytime soon. The U.S. and its allies have stationed a task force in the area and launched airstrikes to secure the zone but the attacks have continued. So, for the time being, commercial vessels have opted to use the longer loop around South Africa to avoid the Red Sea.

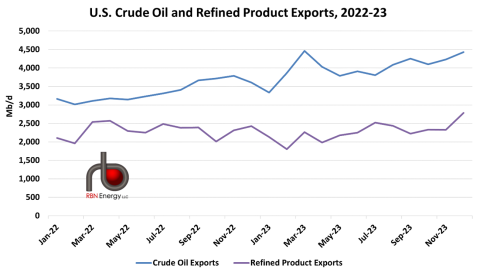

Figure 1. U.S. Crude Oil and Refined Product Exports. Source: Kpler

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article