The Biden administration recently announced a very ambitious — to say the least — rule on tailpipe emissions. But while the rule’s legal and political standing might be a bit uncertain — it’s seen by many as a de facto ban on conventionally fueled cars and trucks and is likely to face several court challenges — doubts also remain about whether it matches up with the realities of today’s energy world. In today’s RBN blog, we look at the new rule, what it would mean for U.S. consumers and automakers, and how it conflicts with the views of RBN’s Refined Fuels Analytics (RFA) practice on the future of global oil and refined products demand and the rate of electric vehicle (EV) adoption.

The push to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the transportation sector has been a key piece of President Biden’s climate agenda since taking office in 2021. His administration has a two-track strategy aimed at the auto industry: (1) make sure cars and trucks use less gasoline, and (2) make sure the vehicles on the road produce fewer emissions.

To achieve the first goal, the National Highway Transportation and Safety Administration (NHTSA) has sought to improve the fuel efficiency of U.S. passenger vehicles and light trucks through changes to Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) requirements. The agency in 2022 amended the rules for the 2024-26 model years to require a fleet average of 49 miles per gallon (mpg) by 2026, increasing efficiency requirements by 8% annually for the affected model years. (CAFE standards for 2021-26 passed by the Trump administration called for 1.5% annual increases.)

NHTSA followed that up in July 2023 with its proposal to increase the nationwide fleet average to 58 mpg by 2032 in its rules to cover the 2027-32 model years. Under that proposal — for which a final rule has yet to be published — CAFE standards for passenger vehicles would climb by 2% per year, while light trucks would see 4% annual increases. Note that CAFE requirements use a different methodology to determine fuel economy than that used by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) when calculating the mpg number on a vehicle’s window sticker. As a result, the CAFE fuel economy is typically considerably higher than what is displayed on the window sticker. Also note that EVs receive very favorable treatment in the CAFE rules, but this could change going forward. (A link to the proposed rulemaking, issued in April of last year, is available here.)

To achieve the second goal — that is, to minimize emissions — the EPA in April 2023 rolled out an aggressive proposal to reduce tailpipe emissions and speed the transition to EVs. (The Biden administration hopes that EVs and plug-in hybrids will account for half of U.S. new-car sales by 2030. Hybrids of all types accounted for about 10.5% of sales in Q4 2023; EVs accounted for another 8.1%.) The EPA proposal called for 13% annual average pollution cuts and a 56% reduction in projected fleet average emissions through 2032 (compared with 2026 requirements) for passenger vehicles and light trucks. (The EPA also proposed stricter emissions standards for medium-duty and heavy-duty trucks through 2032.) The EPA said the rules would reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by more than 9 billion tons through 2055. These rules, interestingly, do not account for GHG emissions from the electricity produced to power EVs. Rather, EVs are counted as having zero GHG emissions, even though electricity production can be a GHG-intensive process.

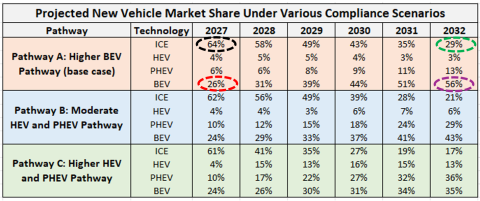

Figure 1. Projected New Vehicle Market Share Under Various Compliance Scenarios. Source: EPA

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article