Globally, government policies have shifted away from petroleum in recent years toward lower-carbon alternatives such as renewable fuels and electric vehicles (EVs), largely driven by worries about climate change. This has pushed down investment in petroleum refining, and RBN’s Refined Fuels Analytics (RFA) practice predicts global net refining capacity will increase by only 2.1 MMb/d, or 422 Mb/d annually, from 2025-29 — the slowest rate in 30 years. In today’s RBN blog, we’ll discuss the upcoming refinery closures, proposed projects, and the obstacles new and existing refiners face.

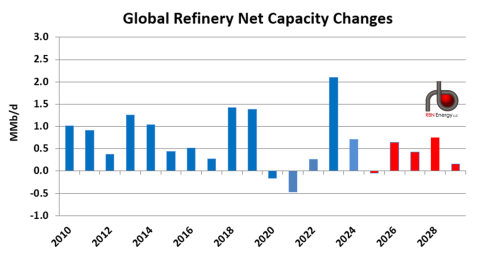

First, let’s look at recent history. A significant amount of global refining capacity (more than 3.8 MMb/d) has been permanently shut down since the start of 2019, primarily triggered by COVID-related lockdowns and the resulting (and unprecedented) drop in demand. These facilities were mainly “non-core” or uncompetitive plants that would have been shuttered in the coming years because of ESG/energy transition factors and declining competitiveness. The facilities closed were primarily in developed countries (U.S., Europe, and Asia). Net capacity additions bounced back to a decades-high 2.1 MMb/d in 2023 after the COVID lockdowns ended and a number of delayed projects finally reached startup. However, that comeback is proving short-lived as net growth fell to 700 Mb/d in 2024. We expect 2025 to decline slightly as the project pipeline empties and additional existing capacity begins to close its doors.

So, why do we have such a pessimistic view on future refining capacity growth and the thinning inventory of credible projects? Several factors are proving to be stumbling blocks for new refining projects and, more importantly, preventing them from reaching the finish line. As we noted earlier, the main hurdle is the push to transition away from petroleum and toward lower-carbon forms of energy. Many countries have added new policies to encourage renewable energy and discourage petroleum usage, leading to a significant slowing of demand growth for refined products and an approaching “demand peak.” These policies and regulations have made investing in petroleum refining more difficult, time-consuming and expensive. The energy transition (aided significantly by flat-to-declining populations) will continue to proceed faster in developed countries where demand is well past the peak, such as Europe and Japan, or where demand is topping out, such as the U.S. In these countries, refining capacity is expected to decline as demand falls. But even in some regions where demand growth continues, particularly China and the Middle East, there is a major shift away from fuels-based refinery projects.

There are still some lockdown-delayed projects starting up, and we see total capacity additions of more than 1.3 MMb/d in 2025, but significant shutdowns are resulting in a net decrease in refining capacity of about 50 Mb/d this year. We predict a net addition of only 2.1 MMb/d over the next five years (red bars in Figure 1 below), with 3.7 MMb/d of new capacity balanced out by 1.6 MMb/d of planned shutdowns. This averages to just 422 Mb/d per year — the lowest five-year-rolling average since 1995.

Figure 1. Global Refinery Net Capacity Changes

Sources: Historical Energy Institute (formerly BP) Statistical Review, 2024; RFA

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article