A primary objective of the federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), when it was expanded back in 2007, was to stimulate by 2022 the production of at least 16 billion gallons/year of gasoline and diesel made from cellulosic biomass in conversion plants resembling small refineries. After getting lots of headlines in the early days of renewable fuels, that vision faded into the background and attention shifted to the use of ethanol in gasoline and the production of diesel from soybean oil, but cellulosic biofuels — non-food crops and waste biomass like animal manure, corn cobs, corn stalks, straw and wood chips — are back in the spotlight thanks to a regulatory quirk. In today’s RBN blog, the first in a series, we review the unusual history of the D3 Renewable Identification Number (RIN), the subsidy designed to stimulate cellulosic biofuel production, and the recent impact on heavy-duty trucking.

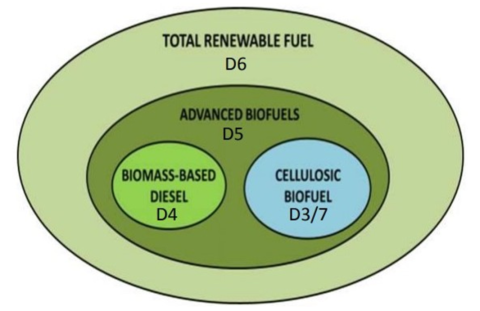

The RIN has long been the tool to force renewable fuels derived from biomass into U.S. gasoline and diesel. A creation of the RFS, RINs act as a variable subsidy that enables profitable production of mandated minimum volumes of renewable fuels that would not otherwise be economically justified. The RIN subsidy is funded by a tax on the supply of petroleum-derived gasoline and diesel to the U.S. transportation market. The RIN is also a financial asset that is traded in secondary markets, where RIN prices are set by the workings of supply and demand. There are four basic types of RINs. The D6 RIN applies to the blending of corn-based ethanol into refined gasoline but also includes the other types of biofuel production, as shown in the RIN “nesting scheme” illustrated in Figure 1 below (see The Big Bang Theory). The D5 RIN includes advanced biofuels; within that group are the D4 RIN (biomass-based diesel) and the D3/D7 RINs (cellulosic biofuel and cellulosic diesel, respectively). Each category has its own mandated minimum volumes of annual production, set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which generally increase over time. (See our Misunderstanding series and Land of Confusion Drill Down Report for more about how the system works.)

Renewable Fuel Categories Under the Renewable Fuel Standard

Figure 1. Renewable Fuel Categories Under the Renewable Fuel Standard.

Source: House of Representatives Energy and Commerce Committee

By design, the market price of a RIN adjusts to the level that provides the necessary incentive to stimulate production of the mandated volume of its corresponding biofuel. But in the case of cellulosic biofuel, it became clear early on that this market-based mechanism would not work — the cellulosic biofuel market never got off the ground. In 2024, the U.S. is expected to produce only 1 billion gallons of the originally targeted 16 billion gallons/year. Why? Because high costs and other barriers (technical, economic and political) to large-scale production of gasoline from wood chips — long viewed as the most logical and economic feedstock — have proved to be more daunting than anticipated back in 2007. (We’ll go into more detail on that in Part 2.)

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article