Natural gasoline is the most expensive natural gas liquid (NGL), accounting for more than 25% of the price-weighted NGL barrel (versus 10%-12% of the barrel by volume). It is also notoriously difficult to track, with similar products having different names and unclear demand segments. In fact, the difficulty tracking portions of demand, combined with an ongoing imbalance in crude oil supply/demand, led the Energy Information Administration (EIA) to change the way it accounted for natural gasoline demand, which made more than 200 Mb/d of production “disappear” in 2022. In today’s RBN blog, we look at natural gasoline’s primary uses and what was behind the EIA’s decision.

In yesterday’s blog, we discussed some of the quirks of natural gasoline, specifically how several components with similar molecular makeups are all labeled differently. We also said that production of natural gasoline has increased considerably since the early days of the Shale Revolution; that it is the only NGL with seasonality in production; that it is the heaviest product in the mixed NGL stream produced at gas processing plants; and that it is the heaviest cut from an NGL fractionator. Oh, and we said that the name — natural gasoline — comes from its source and its qualities: It is “natural” because it comes from natural gas, not a refinery. And it is “gasoline” because it is similar in quality to very low-quality motor gasoline.

Natural gasoline is defined as the part of the natural gas stream containing mostly pentanes, but also some hexanes and heptanes+ (C5, C6, C7, and heavier). It has four primary uses:

- Motor gasoline blending. This is the original use for natural gasoline. The product has a low octane rating of 60-80 RON — or research octane number — versus the 87-93 RON required in most motor gasoline. It also has a relatively high vapor pressure, typically between 8 and 15 pounds per square inch (psi; see Tank Full of Butane for more about RVP and motor gasoline blending). The sulfur content of natural gasoline can vary, with some streams having a high sulfur content and others having a low content. The specification for sulfur in natural gasoline is 30 parts per million (ppm) versus that of motor gasoline (10 ppm). To reach the specification of motor gasoline, Targa Resources and Enterprise Products Partners have desulfurization plants specifically for natural gasoline. (For more on sulfur regulations, see Tears of a Refiner.) So why does it get used in motor gasoline at all? Well, because it is a good value. In today’s market, natural gasoline is priced at roughly 122 cents/gallon (c/gal) versus 195 c/gal for unleaded gasoline (87 octane). That means that a blender using natural gasoline as a blendstock can sell that gallon at a 73 c/gal premium.

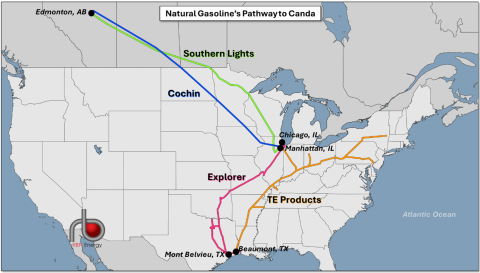

- Diluent for Heavy Canadian Crude. Natural gasoline plays a critical role in the transportation of heavy Canadian crude oil, particularly bitumen from Alberta’s oil sands. Due to its high viscosity and density, bitumen cannot flow through pipelines in its raw form. To reduce its viscosity and meet pipeline specifications, bitumen gets blended with lighter hydrocarbons, known as diluents, to create diluted bitumen (dilbit). Among the various diluents used, natural gasoline (also called pentanes plus or C5+) is a key choice due to its availability, cost-effectiveness and relatively low molecular weight and high API gravity. The high API gravity generally implies lower viscosity for the blend, which makes the heavy crude from oil sands flow more easily through pipelines. The U.S. plays an important part in the diluent market in Canada; roughly one-third of the diluent used to transport Canadian oil sands crude is imported from the U.S., with the rest coming from local NGL and condensate supply in Western Canada. Natural gasoline from the U.S. travels a long way, going up the Explorer Pipeline (pink line in Figure 1 below) and TE Products line (still referred to as TEPPCO by much of the industry) from Mont Belvieu and Beaumont, respectively. Around the Chicago area, the volumes make their way onto Enbridge’s Southern Lights (green line) or Pembina’s Cochin Pipeline (blue line) to Alberta. And just to make things confusing — just kidding! — Canadians call natural gasoline condensate, and sometimes plant condensate, to differentiate it from field condensate. (See Every Time I Turn Around for more about condensate’s use in Canada.)

Figure 1. Natural Gasoline’s Pathway to Canada. Source: RBN

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article