Rapid growth in U.S. gas exports to Mexico already is having profound effects north of the border, and things will only get more interesting. Gas producers in the Eagle Ford and other Texas shale plays are finding the new buyers they need. But gas consumers in the Southwest—caught with a losing hand of stagnant regional gas production, rising gas demand, increasing gas exports to Mexico, and pipeline capacity tightness—face potentially serious delivery concerns and price premiums in the not too distant future.

|

Check out Kyle Cooper’s weekly view of natural gas markets at http://www.rbnenergy.com/markets/kyle-cooper |

In Part 1 of “U.S. Gas Heading Way Down South, Way Down to Mexico Way”, we looked at what’s driving growth in Mexican gas demand, why increasing amounts of Texas gas are needed to supplement Mexico’s domestic production, and where all the new cross-border and in-Mexico pipeline capacity is being built to allow for the big southward gas pull. In Part 2, we again turn to Bentek’s report, “Growing Mexican Gas Market Creates Southwest Price Premiums,” to help us sort through what the new Texas/Mexico dynamic means for Texas gas producers and gas consumers in the Southwest. We also consider how the current dynamic may shift over time, and what might cause the shifting.

Mexican demand for gas is expected to rise by 30%, or 2.7 Bcf/d, by 2018, mostly due to new gas-fired power plants there. Increased gas production within Mexico will provide 1 Bcf/d of the incremental gas needed, but with LNG imports expected to remain flat, U.S. gas producers will need to provide the remaining 1.7 Bcf/d Mexico will require. That means U.S. gas exports to Mexico will nearly double—from 1.9 Bcf/d this year to 3.6 Bcf/d in 2018, with much of the incremental exports expected to flow south past existing pipeline constraints or choke points on Kinder Morgan’s El Paso Natural Gas pipeline system.

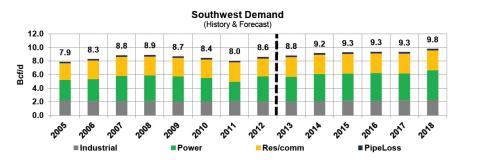

That might be ok if gas demand in the Southwest were not expected to grow by 1 Bcf/d, to 9.8 Bcf/d, over the next five years, mostly due to the planned replacement of coal-fired and nuclear capacity with new gas-fired power plants (see Figure 1). It also might be manageable if gas production in the Southwest were rising, and not remaining flat, at about 4 Bcf/d, or if Southwest gas exports to Mexico were not expected to increase by 0.9 Bcf/d. But with the need to bring more gas in from Texas, the Rockies and the Pacific Northwest, the Southwest faces the possibility of a real pipeline capacity squeeze.

Figure 1 (Click Image to Enlarge)

Nine major gas pipelines tie into the Southwest from the three neighboring regions, providing a combined inflow capacity of 8.8 Bcf/d. Grouped by region, they include Redwood Path, Tuscarora and Paiute from the Pacific Northwest; Kern River, Northwest, TransColorado and Southern Trails from the Rockies; and El Paso and Transwestern from Texas. Two other pipelines send Southwest gas to Texas: Northern Natural and NGPL. And the Southwest can receive regasified LNG from the Costa Azul LNG terminal in Baja California via the North Baja pipeline, but in recent years, with increasing gas flows from the U.S. to Mexico, there has been talk of turning Costa Azul into an export terminal.

Gas pipeline capacity into the Southwest from the Pacific Northwest and the Rockies is close to maxed out, says Bentek. Flows through the four pipelines from the Rockies, for example, in 2012 averaged 2.6 Bcf/d, or only 0.6 Bcf/d less than the lines’ combined 3.2 Bcf/d capacity, and at times the spare capacity dropped to as little as 0.2 Bcf/d. The three Pacific Northwest pipelines into the Southwest also have been running at high utilization rates. Last year, an average of 2.2 Bcf/d flowed along the lines, leaving only 0.2 Bcf/d of capacity unused. Gas flows from Texas to the Southwest, meanwhile, netted (outflows less inflows) an average 0.4 Bcf/d in 2012, with El Paso moving 1.4 Bcf/d out of Texas, and Transwestern, Northern Natural and NGPL moving 1 Bcf/d of Permian and San Juan basin gas from the Southwest into the Lone Star State.

Most of the current open pipeline space into the Southwest is along the Texas corridor (El Paso and Transwestern) which together have the capacity to deliver up to 3.4 Bcf/d but, as noted above used only 1.4 Bcf/d which leaves 2 Bcf/d of capacity up for grabs. So what’s the problem for the Southwest? First of all, Transwestern’s pipeline runs nearly full west of Thoreau (in west-central New Mexico) with San Juan Basin and Rockies gas, so its 0.8 Bcf/d of available pipeline capacity out of Texas can’t be used to move Texas gas to Arizona, Nevada or California. Also, higher reservation fees charged for long-haul capacity on El Paso—combined with higher supply costs in the Permian Basin—have hindered capacity agreements with Southwest markets. The bottom line is this: If Mexican markets sign up El Paso pipeline capacity first, they will lock Southwest buyers out. Each cubic foot of exported gas will fill a portion of the capacity at the key Cornudas compressor station, effectively removing that pipeline space for gas moving into the Southwest. No expansion at Cornudas is currently planned.

Total gas inflows into the Southwest averaged 5.2 Bcf/d in 2012—considerably below the total inflow capacity of 8.8 Bcf/d. But within five years the inflows needed to meet the Southwest’s demand could exceed 7 Bcf/d (see Figure 2), and because of the El Paso constraints there could be tight supply conditions and price spikes.

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article