The 1,413-MW Mystic Generating Station, a longtime workhorse for New England, shut its doors for good May 31. Located in Charlestown, MA, on the north side of Boston, Mystic is adjacent to the Everett LNG terminal, which supplied 100% of Mystic’s natural gas for several decades. The power plant’s closure meant the Everett terminal might also be history. However, the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities (DPU) recently approved new contracts that will keep Everett LNG open for at least six more years. In today’s RBN blog, we’ll discuss the combined impact of Mystic’s demise and Everett’s stay of execution, how the region has handled this summer’s heat wave, and what could be in store for next winter.

The Everett LNG import terminal and the Mystic Generating Station are linked by more than proximity. Constellation Energy, which owns both facilities, initially planned to close ’em both. Mystic was the largest, most strategically located gas-fired plant in the six-state region, whose electric grid is overseen by ISO New England (ISO-NE), the regional transmission organization (RTO). In 2018, Mystic’s then-owner, Exelon Corp., filed its intention with ISO-NE to retire the plant by June 1, 2022, stating it could no longer operate it and turn a profit. ISO-NE, in turn, said the units at Mystic were essential for fuel and system reliability in the Greater Boston area and required the plant to remain open through May 31, 2024.

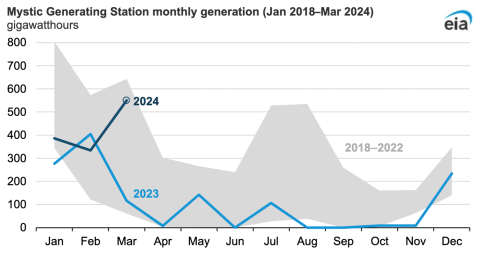

In recent years, Mystic has served largely as a backup power generator during periods of extreme heat or cold when electricity is in high demand. (Mystic was built in the 1940s and was one of the oldest gas-fired power plants in the U.S., leading to inefficiency, increased operational costs and lower dispatch rates. An analysis by ISO-NE in 2023 showed that electricity customers in the region paid $536 million over 2022-23 to keep the station operational.) The gray-shaded area in Figure 1 below shows the range of its monthly output in gigawatt-hours (GWh) in the 2018-22 period (when it generally operated at about 20% of its rate capacity), while the blue line shows its minimal output through most of 2023 (averaging less than 10% of its rated capacity) and the black line its modest output in the first three months of 2024. Executives at Constellation held steady on their wishes to close the plant, maintaining that it was no longer cost effective. Still, Mystic had the potential to generate enough power for nearly 1.5 million homes if and when that power was needed.

Figure 1. Mystic Generating Station Monthly Generation. Source: EIA

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article