The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) proposed Renewable Volume Obligations (RVOs) for 2026-27 did more than just set renewable fuel mandates for the next two years, they included dramatic shifts in the way that imported fuels and feedstocks are handled and raised the likelihood of higher compliance costs during a time in which the federal government has been focused on keeping prices under control. In today’s RBN blog, we look at the critical changes that will affect imported biofuels and feedstocks and the potential cost impact.

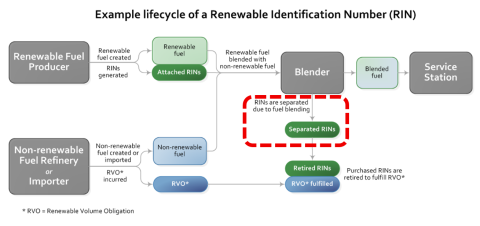

Let’s start with a bit of background about how the mandates for renewable fuels work. As we noted in Something’s Gotta Give, the federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) requires certain minimum volumes of biofuels to be blended into fuel sold in the U.S. The required minimum, known as the RVO, is determined each year by the EPA. A Renewable Identification Number (RIN) is the regulatory mechanism for tracking the production and blending of renewable fuels and also allows refiners and importers to prove they’ve met their RVO mandates. A RIN is a 38-digit-number created when a gallon of biofuel (ethanol, biodiesel, renewable diesel, etc.) is manufactured. Once that biofuel is blended for sale in the U.S. (dashed red box in Figure 1 below), the RIN becomes “detached” from the biofuel, and two things can happen: (1) it can be surrendered to the EPA by an obligated party (a refiner or importer of gasoline or diesel) to demonstrate compliance with the RFS, or (2) if a non-obligated party generates the RIN, they can sell it to obligated parties who then surrender it to the EPA to meet their obligation. (Note that the RIN lifecycle differs slightly for fuel exporters.) As we detailed in our Misunderstanding series, RINs essentially act as a mechanism with elements of a tax and a subsidy to force renewables into fuels.

Figure 1. Example Lifecycle of a Renewable Identification Number. Source: EPA

It’s important to note that obligated parties cannot fully satisfy their RVOs just by blending renewable fuel into E10 gasoline, the 90-10 mix of conventional gasoline and ethanol typically available at the pump. There are two reasons for this. First, the RFS blending mandates require that the overall gasoline pool contain more than 10% ethanol, so E10 blending alone is insufficient, meaning that more of the RVO needs to be met with other biofuels. (Conventional biofuels, usually corn-based ethanol, generate a D6 RIN.) Second, any gasoline or unfinished gasoline (such as CBOB and RBOB) produced by a refinery also generates an obligation for biomass-based diesel, which cannot be blended into gasoline — E10 or otherwise. That makes the production of fuels such as biodiesel (BD), renewable diesel (RD) and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) — which produce a D4 RIN — critical to the RFS. (As we detailed in Big Bang Theory and shown in Figure 2 below, the EPA’s “nesting” approach to RINs allows higher-standard fuels to be used to meet requirements for broader, lower-standard categories, a structure designed to promote flexibility. For example, a D4 RIN can also satisfy compliance for D5 and D6 RINs, maximizing the options for obligated parties.)

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article