Anyone in the energy business knows that the growth of natural gas production in the Northeast US this decade, particularly in the Marcellus basin, has been a real game changer. Northeast production last month (September 2012) reached 9 Bcf/d. That includes both Marcellus and legacy Appalachian production. The huge increases in volumes have provided big challenges and opportunities in every segment of the energy business. Today we introduce a blog series looking at how natural gas companies are redefining their strategies, infrastructure and operations in response to these dramatic changes.

Let’s start with a snapshot of conditions just prior to the Marcellus phenomenon. The Northeast market for natural gas was primarily a consuming area with less than 1.8 Bcf/d of local Appalachian gas production. Local distribution companies (LDCs) therefore focused on delivering gas to the region via large interstate pipelines (primarily the three “T”s - Tennessee, Transco and Texas Eastern) and then redistributing the gas to consumers they served including residential and commercial, industrial users and power generators. The LDCs purchased gas from a variety of sources including Gulf Coast receipt points on the three “T”s, other Gulf/Midcontinent pipes and Canadian import points including Niagara and Waddington.

LDCs utilized transportation contracts they entered into on a long-term basis to deliver gas to their city gates and to market area storage during non-peak periods. Since the long haul pipelines were not sized to deliver enough gas to meet the demands of cold winter days, withdrawals from storage when combined with current transports enabled LDCs to meet these peak demands during the November to March heating season. Utilization of market area storage was economic to lower the average cost of gas by filling storage during the summer when gas was cheaper and enabled LDCs to better utilize pipeline capacity during the summer when demand was lower. This resulted in a higher average load factor. (Note: load factor means the ratio of volume transported divided by total capacity over some period of time, in this case one year.) Constraints during the heating season created price volatility into some markets such as New York City (Transco Zone 6). New England utilities also relied on LNG shipments to meet peak day demand. These were some of the higher priced markets in the country and an attractive target for spot gas supplies.

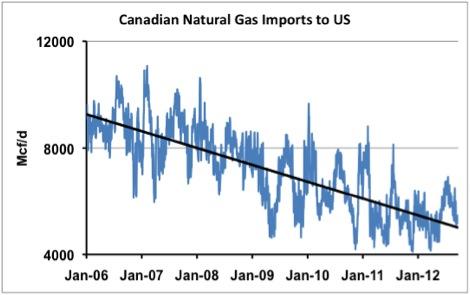

This apparently stable tried and tested transportation system was not fated to last. Rapidly changing supply fundamentals in the past few years have caused gas buyers to rethink their strategies to deal with a myriad of new circumstances in the Northeast. First gas from the Rockies started to look for new markets and the building of Rockies Express (the big 1.8 Bcf/d pipeline from the Rockies to Ohio) caused a number of new downstream pipeline projects to be built with commitments from gas producers and marketing companies in a classic supply push with the hopes of higher net back prices for the producers. These projects would move gas east from the terminus of REX and other pipeline interconnects. At the same time, available imports from Canada were declining (see chart below) for three reasons. First increased domestic demand for natural gas in Canada as a fuel for tar sands production in Alberta required the gas to stay in Canada. Second, demand for gas as a fuel for power generation increased as coal plants in eastern Canada were being converted to natural gas, and third because Canadian gas production from established wells was declining. As a result, imports from Canadian border points such as Niagara and Waddington declined. For a time the market seemed to understand its new direction and rebalancing was underway. Then lo and behold, early drilling in the Pennsylvania portion of the Marcellus shale proved to exceed producer’s wildest estimates and the rush began. Some thought the Wild West was being reinvented in the East.

Source: Bentek Cell Data

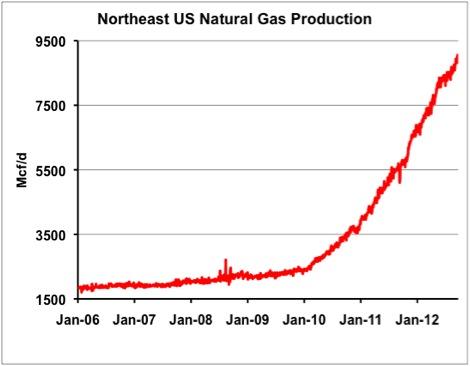

Natural gas wells in the Northeast region were brought on stream and locally produced gas flowed at ever increasing volumes (see chart below). It was so promising that even major oil companies arrived on the scene to participate by buying smaller companies. Production was now in the backyard of one of the largest and most valued natural gas consumer markets in the world. The repercussions of this step change continue to evolve as we see new infrastructure being built. Since local production exceeded the demand in the Northeast market and transportation bottlenecks constrained flow, gas began to be moved from the region to what were previously upstream markets. LNG imports, previously thought to be needed to meet demand in the U.S, vanished and we now look to a future with exports of LNG from the U.S. The value of Northeast storage capacity has declined. Nobody can get too comfortable about what the future will bring. Just as we started to adjust to the Marcellus, we now see the development of the Utica shale and as Yogi Berra said, we have “déjà vu all over again”. New imbalances and infrastructure needs have arisen and more decisions and investments are on the way as gas from the region tries to find a home in and out of the region “squeezing that balloon” and causing other imbalances. Gathering, processing, and pipeline projects abound. Past strategies get questioned and the beat goes on.

Source: Bentek Cell Data

Follow up blog postings in this series will drill down (no pun intended) on these developments and issues to look at how gas will likely flow in the future and the effect that will have on players in the gas industry.

Each business day RBN Energy posts a Blog or Markets entry covering some aspect of energy market behavior. Receive the morning RBN Energy email by simply providing your email address – . |