The popularity of weather derivatives has ebbed and flowed since their introduction in the late 1990s but trading activity has rebounded in recent years as the trading community has increasingly begun to reassess the need to hedge weather-related risks — everything from high temperatures and rainfall levels to power prices and cooling demand. In today’s RBN blog, we examine the role of weather derivatives, how they are used to hedge risk, and why they may be becoming increasingly important to the energy industry.

Many of you are probably familiar with Jim McIngvale (see photo below), the Houston-area celebrity known as “Mattress Mack” and the owner of Gallery Furniture. He gained national attention back in 2017 when he opened his stores to those affected by Hurricane Harvey, but he’s also attracted a lot of notoriety for his big-dollar bets on college and professional sports. We assume that Mattress Mack enjoys a good wager and the publicity that comes with it, but there’s often a bottom-line strategy behind his bets. In perhaps the most newsworthy example, his stores ran a promotion back in 2022 that said if you bought at least $3,000 in furniture, you’d get it for free if the Houston Astros won the World Series. That potentially expensive proposition became a reality when the Astros beat the Philadelphia Phillies in six games, but Mattress Mack was covered because the downside risk of that promotion (giving away a lot of free furniture) was hedged by his bet on the Astros to win the Series. In the end, he won a reported $75 million in bets (on $10 million wagered), earned himself and his store a load of free publicity, and more than made up for all the free furniture he ended up giving away.

Houston’s Jim McIngvale, Better Known as “Mattress Mack.”

Weather derivatives, which have been around for about 30 years, work in much the same way as the example above, so let’s start with some basics. Weather derivatives are financial contracts that are linked to one or more specific, measurable variables, such as average temperatures, wind speeds and cumulative rainfall. They are financially settled using data from the National Weather Service (NWS) or other trusted, third-party providers. Perhaps most importantly, there is no physical damage required to trigger a payout (unlike insurance); the only thing that matters is whether the specific conditions of a derivative have been met. For example, a business impacted by the aforementioned Hurricane Harvey would have had to document any actual damage and file a claim for its insurance to pay out but could have quickly collected on any derivatives tied to above-average rainfall for that month. (Harvey dropped 40-50 inches of rain on Houston in August 2017, well above the monthly average of 5.4 inches.)

Weather derivatives are fully customizable with the same structures found in other types of derivatives. We don’t want to get too far into the complex world of trading, but let’s look at some of the relevant terminology in a basic example. Let’s assume that, to protect itself against the effects of a warmer-than-expected summer month, a utility buys a cooling degree day (CDD) call option for a specific month with a strike of 270 CDDs and a tick price of $10,000. (The strike is the threshold at which payments begin. The tick price is the payout per unit. CDDs are a measure of how much air conditioning is required to keep temperatures at 65 degrees Fahrenheit.) If CDDs came in at 300, that would be 30 units above the strike and the utility would receive a payout of $300,000 (30 * 10,000). If total CDDs ended up below 270, the option would expire with no payout. A put option would have the opposite purpose. If that same utility buys a put option for CDDs with a strike of 270, the utility would receive a payout if CDDs came in below that figure, protecting it from the effects of a cooler-than-expected month. The utility pays an upfront premium for the protection offered in either scenario.

As in any futures trading, there are two groups involved in weather derivatives. First, like the hypothetical utility noted above, there are the hedgers. These are businesses whose profitability is directly and materially impacted by variations in the weather. They use derivatives not to speculate, but to protect their bottom line from adverse conditions. In the energy sector, hedgers could include utilities and power generators, which need to manage fluctuations in consumer demand; renewable energy producers, which are particularly vulnerable to changes in the weather; and oil and gas producers, which often benefit from the high prices driven by extreme weather but are also operationally vulnerable to them (i.e., freeze-offs caused by cold weather and shutdowns due to hurricanes).

Equally important are investors and market makers, who seek profit opportunities in the weather market by taking on the risk that hedgers are looking to avoid. In other words, speculators. These investors are essential to the functioning of weather derivatives because they provide liquidity — the ability to enter and exit the market quickly, easily and efficiently. Investors include every type of participant, including hedge funds, large banks and individual traders. According to our friends at Citadel, the ecosystem operates across two main venues: standardized exchanges like the CME, which offer listed futures and options for common locations, and the over-the-counter (OTC) market. While many are familiar with the listed products, it is the OTC market that represents the majority of weather risk transacted globally. The reason for this is customization. A company’s financial exposure to weather is unique, and an off-the-shelf product is often an imperfect hedge.

Weather derivatives have been around for nearly 30 years, with the first OTC trade occurring in 1996 and CME launching its weather derivative contracts in 1999. The market grew in the early 2000s as CME expanded its derivatives coverage to include 15 U.S. cities and five European cities and hurricane, precipitation and snowfall offerings. Derivatives took a step back around the time of the Great Recession and became more of a niche market, but trading activity has increased in recent years thanks in part to their inclusion on CME’s Globex platform.

Another reason why weather derivatives have rebounded in recent years is that what happens in the energy industry — including power generation (especially wind and solar power) and the stability of the power grid — has become more dependent on weather events. The recent increase in trading coincides with this year’s spike in European natural gas prices, which was caused in part by lower renewable output (along with geopolitical tensions and low storage levels).

Let’s look at how a weather derivative could function in real life, using the example of a Dallas-based data center. The operator in our hypothetical scenario has a power purchase agreement (PPA) to cover its electricity needs at a fixed price, but it is exposed to variable energy demand driven by the summer heat. High temperatures could cause the site’s cooling-related power usage to increase sharply, even if the cost of the power itself under its PPA did not move higher. (As we’ve noted in previous blogs, cooling costs are one of a data center’s major expenses, especially for those located in Texas and other warm climates.) To hedge that exposure to high temperatures, the operator could pursue a call option based on CDDs, much like the basic example we noted above.

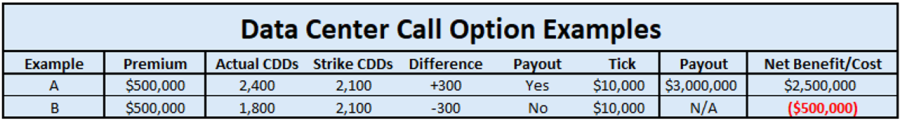

In this scenario, the operator’s call option is for a specific period of time (May through September), using data from a specific National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) location in Dallas, at a strike of 2,100 CDDs across the term of the contract, with a tick size of $10,000 per CDD, and the overall payout capped at $10 million. The cost of the premium is $500,000. Figure 1 below has two potential outcomes, one where the number of CDDs is above the strike and one where it is below.

Figure 1. Data Center Call Option Examples

In Example A, the number of actual CDDs for the May-September period comes in at 2,400, or 300 above the strike in the operator’s call option. That results in a payout of $3 million based on the number of additional CDDs and the tick price (300 * $10,000) and a net benefit of $2.5 million (after factoring in the cost of the contract), which allows the operator to successfully hedge at least some of its increased cooling costs during those five months.

Of course, if the number of actual CDDs comes in below the strike, as in Example B, there is no payout under the contract. Just like with insurance, you pay the premium but end up with nothing to show for it if the weather doesn’t cooperate, leaving only the cost of the hedge behind.

That’s a pretty straightforward approach to hedging weather risk, but things can get a lot more complicated than that. In our next blog, we’ll look at how weather derivatives can tie together multiple variables into a more complex hedging strategy.

“Chances Are” was written by Robert Allen with lyrics by Al Stillman. It appears as the first song on side one of Johnny Mathis’ 1958 compilation album, Johnny’s Greatest Hits. Released as a single in August 1957, it went to #1 on the Billboard Most Played by Jockeys and #5 on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles charts. Music critic Robert Christgau wrote that the song “projected an image of egoless tenderness, an irresistible breath of sensuality.” It was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1998 and was selected for inclusion in the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress in 2024. The record is close to perfection on every level. Mathis’ smooth vocals, Ray Coniff’s lush arrangements and Dick Hyman’s perfect piano arpeggios laying on top of the chord changes make for a stellar listening experience. It was recorded at Columbia 30th Street Studio in New York City in June 1957 and produced by Mitch Mitchell and Al Ham. Personnel on the record were: Johnny Mathis (vocals), the Ray Coniff Orchestra (orchestrations) and Dick Hyman (piano).

Johnny’s Greatest Hits is a compilation album of singles Mathis recorded at Columbia 30th Street Studio in New York City between 1956 and 1958. Produced by Mitch Mitchell and Al Ham, the album was released in March 1958 and went to #1 on the Billboard 200 Albums chart. The album was compiled from 12 previously released Mathis Singles.

Johnny Mathis is an American singer whose catalog focuses on romantic American Standard songs. He cites Lena Horne, Nat King Cole and Bing Crosby as his influences. He started singing while attending George Washington High School in San Francisco, where he was a star athlete. He then attended San Francisco State College on an athletic scholarship. He started singing in San Francisco nightclubs in 1955 and released his debut studio album on Columbia Records: Johnny Mathis: A New Sound in Popular Music, in 1956. He has released 73 studio albums, three live albums, 30 compilation albums and 113 singles. He is in the Grammy Hall of Fame, the Great American Songbook Hall of Fame, has a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. At 89, Mathis has retired from performing and gave his last concert at the Bergen Performing Arts Center in Englewood, New Jersey, in May.

Comments

Chances Are

Is there a figure missing from this blog? The text says:"The recent surge in trading (far-right blue bar in Figure 1) coincides with this year’s spike in European natural gas prices, which was caused in part by lower renewable output (along with geopolitical tensions and low storage levels)." But, there is no figure with a blue bar.

Thank you for reading and

Thank you for reading and catching that error. The text has been updated.