I was working in the lab late one night…

First came gas from fracking shale, then liquids from fracking shale then Canadians diluting bitumen. Now we have too much gas and everyone wants to turn gas back to liquids. I knew I should have majored in chemistry. [posted by contributor Sandy Fielden]

In today’s blog we describe plans being touted to build two huge processing units in Louisiana to transform natural gas into refined oil products – a process known as gas-to-liquids or GTL. If the technology makes operational and economic sense, it could be a huge contributor to natural gas demand and help relieve some of the supply overhang. But this technology has been around for a long time, and it sounds a little pie-in-the-sky. So we’ll look under the covers at the chemistry involved (from a layman’s perspective) and do our best to rough out the economics of these facilities.

The Chemists

Two energy companies have successfully developed GTL technology to production scale. They are South African GTL pioneer Sasol and oil major Royal Dutch Shell.

Sasol Ltd. announced in September 2011 that they have selected a site in southwest Louisiana as a possible location for a multibillion-dollar plant that converts natural gas to diesel and other products. The company will conduct an 18-month feasibility study that weighs the regulatory process, “supply issues,” capital costs and other factors before it decides whether to proceed. If the Sasol plant proceeds as planned, construction is expected to start in 2013, and the complex would be built in two phases that upon completion in 2018 would process approximately 4 million tons of products per year, with a maximum capacity of 96,000 barrels per day.

In early April 2012 the Wall Street Journal reported that Royal Dutch Shell PLC is also considering building a giant plant in Louisiana to convert natural gas to diesel. The plant, which could cost more than $10 billion, would be similar in size to Shell's Pearl gas-to-liquids facility in Qatar. The Pearl GTL plant is the world’s largest and made its first commercial shipment in June 2011. The Pearl plant is expected to reach full capacity in 2012 – converting 1.6 BCF a day of natural gas into 140,000 barrels of petroleum products (primarily naphtha).

The Chemistry

Gas-to-liquid units are based on something called the Fischer-Tropsch process. The technology was first used by Germany to turn coal into oil in the 1920’s. The process was then fine-tuned by South Africa in the 1970’s.

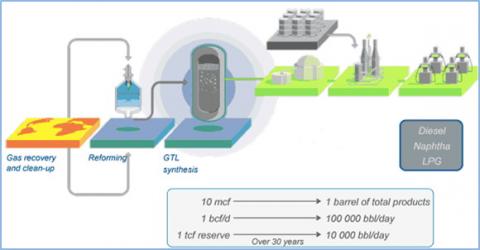

How does it work? At the most basic level, Fischer-Tropsch uses chemical reactions to convert natural gas into liquid petroleum products. The process starts by oxidizing dry natural gas (methane, CH4) to create a mixture of carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2) Hydrogen (H2) and water (H2O). The excess carbon dioxide and water is removed and the carbon monoxide hydrogen ratio is adjusted to yield a synthesis gas. The synthesis gas is chemically reacted over an iron or cobalt catalyst to produce liquid hydrocarbons that are then be treated in a refinery cracker to produce various petroleum products (See the figure below for a flowchart of the process.) Got that?

The Economics

The Sasol website is more forthcoming about the economics than Shell. The proposed Sasol plant in Louisiana would produce nearly a hundred thousand barrels of petroleum products in the ratio of 80% diesel, 15% naphtha and 5% propane. The diesel output is a high value middle distillate with close to zero sulfur content – currently very attractive to European markets. The plant would consume 1 bcf/d of dry natural gas or 10 mmbtu per barrel of product (see Sasol flow diagram below).

Looking at historical prices the plant output sales prices (based on diesel, naphtha and propane prices in the US Gulf) looks increasingly healthy because the spread between refined products and natural gas has widened dramatically since early 2009. (see graph below). As of April 26, 2012 the margin (not including operating costs) was around $108 per barrel. Back in January 2009 however, it was close to $0.

Two factors are critically important in plant economics. The first is the high capital cost of the plant. Sasol estimates a plant cost of $10 billion (more expensive than a traditional oil refinery). Over a 30 year period, the finance charge on $10 billion at a conservative 5 percent interest works out close to $4 million a day.

The second factor is the price spread risk – the risk that natural gas prices do not stay low and that refined product prices do not stay high. If the current spread narrows back to where it was at the start of 2009, plant profitability disappears.

Plant Economics Examples

Let’s look at some very loosey-goosey, back-of-the-envelope numbers to put this in perspective. If we assume variable operating cost (fuel, catalysts, humans, etc.) of $10 per barrel, then the daily economics of running the plant on April 26, 2012 are shown in the first table below. If we look at the same numbers back on January 1 2009, the picture in the second table is not so rosy.

Conclusion.

I seriously doubt I could ever find a bank willing to lend me $10 billion, but even if I could, I’m not sure I’d feel good about using the money to build a GTL plant. The economics look great today, but the volatile price environment makes the 30 year investment look quite risky. It would be tough hedging the margin using NYMEX natural gas and heating oil contracts for more than a few years out. It would be unlikely that they could get to the startup time of the plants, much less further out in the economic life. Perhaps the owners can lock in gas supply over a longer period at a fixed price by buying up gas from producers anxious to ditch unwanted dry gas? Hey producers, anyone want to sell your gas indexed to diesel?

BTW, if any of you youngsters are having trouble understanding the title for this one, click MONSTER MASH.

Each business day RBN Energy posts a Blog or Markets entry covering some aspect of energy market behavior. Receive the morning RBN Energy email by simply providing your email address – click here. |

Comments

GTLs

Sandy,

Excellent summary of GTLs economics.

Thanks!