In the early 2000s, prices for West Texas Intermediate (WTI) were becoming increasingly disconnected from global fundamentals. WTI reflected conditions in the Midcontinent at the Cushing, OK, crude oil storage hub, where bottlenecks repeatedly distorted its value. In today’s RBN blog, we look at how the problem contributed to the creation of the Argus Sour Crude Index (ASCI) 16 years ago, how the index has evolved and whether it remains relevant today.

In the years before the ASCI, Saudi Aramco had a problem. The official sales prices (OSPs) of their crude were linked to WTI, a volatile light sweet crude whose price reflected Midcontinent imbalances, even though many refiners on the Gulf Coast, where their crude was being imported, were configured to efficiently run a bigger slate of medium and heavy sour barrels. The result was a volatile relationship between the prices of WTI and imported crudes, which impacted the economics faced by Gulf Coast refiners. For Aramco, the solution was to abandon WTI in favor of the ASCI, a benchmark rooted in the sour grades that Gulf Coast refiners actually processed.

When the ASCI (see The Price You Pay) was launched in 2009, its three core Gulf of Mexico (GOM) sour grades — Mars, Poseidon and Southern Green Canyon (SGC) — were the major U.S. medium sour crudes with specifications close to Saudi Aramco’s Arabian Medium, a grade most Gulf Coast refineries were configured to run:

- Mars has an API gravity of about 30.5 degrees and sulfur content near 1.8%. Production at the time averaged roughly 255 Mb/d. Its yields included about 49% residue (the heavier fraction used for fuel oil or further upgrading) and balanced outputs of kerosene and gas oil in the 13%-17% range.

- Poseidon was even heavier and sourer, with an API of 29 and 1.98% sulfur. Output was around 90 Mb/d with similar splits, marked by nearly 20% gas oil and more than 50% residue.

- SGC was somewhat lighter with an API of 30.8 but contained higher sulfur at 2.2%. Production was close to 500 Mb/d with comparable yields, with nearly half the barrel going to residue.

In contrast to those three, WTI was a much lighter crude (39-42 API) with sulfur typically below 0.3%, requiring less-complex refining and yielding larger volumes of more valuable light products such as gasoline and naphtha, while producing significantly less residue. Gulf Coast refiners, however, had invested heavily in complex upgrading units — cokers, hydrocrackers and desulfurization facilities — designed to process medium and heavy sour crudes. These barrels were typically priced at a discount to light sweet crudes, allowing refiners to convert lower-cost feedstock into high-value products and capture stronger margins. This economic reality explains why sour GOM crudes aligned closely with the needs of U.S. refiners, and why Saudi Aramco’s adoption of the ASCI represented a logical break from a benchmark rooted in light sweet inland barrels.

When Saudi Aramco decided in 2009 to move away from WTI as the reference price for its U.S.-bound crude, it was more than just a pricing adjustment. It was a strategic shift that recognized the growing disconnect between paper benchmarks and the physical realities of the Gulf Coast refining system. The ASCI gave U.S. refiners a pricing mechanism that more closely reflected the barrels they processed. By the end of that year, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq had all adopted the ASCI as their benchmark for sales into the U.S. WTI continued to serve as the primary benchmark for domestic U.S. crude pricing and global financial trade, but for Middle East crude imports into the U.S., the reference point had decisively shifted to the ASCI. Financial markets also acknowledged the new benchmark’s role, with CME and ICE introducing futures contracts linked to the index, though trading volumes never matched the deep liquidity of WTI or Brent.

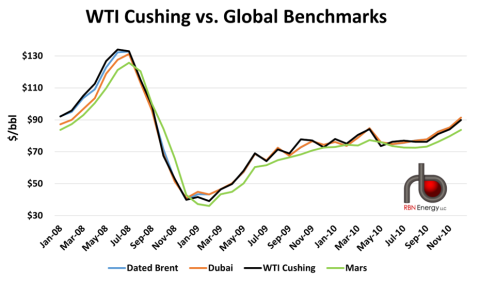

The shift away from WTI was both practical and symbolic. As shown in Figure 1 below, WTI’s price (black line) occasionally diverged from other major benchmarks due to storage bottlenecks in Cushing (see Give and Take). At times, volatility was so severe that even with monthly OSP adjustments, Saudi cargoes priced against WTI landed either too cheaply or prohibitively expensive compared to rival crudes. This was unacceptable for both Aramco and its customers. Also, crude OSPs should be priced based on physical trades rather than financial instruments driven by speculation. The ASCI offered that physical linkage, and it quickly gained credibility as a Gulf Coast benchmark.

Figure 1. WTI Cushing vs. Global Benchmarks. Source: EIA

Join Backstage Pass to Read Full Article